Sudan: what does the Referendum mean?

By Ian Leggett

Last week the citizens of Southern Sudan voted in a historic referendum to determine whether they remain part of a united Sudan or secede. If those who want to secede win the vote – and all the indications are that there has been a landslide vote in favour of separation – the result will be to create one new and independent state, and to redraw the boundaries of the existing state of Sudan to such an extent that it is effectively a new country. That the political future of Northern Sudan will in effect be determined by the decisions of up to four million Southern Sudanese is an irony that has not been lost on the peoples of the north.

The Referendum was one of the most important provisions of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) which brought Sudan’s long and bitter civil war to an end.

That it was held in accordance with the terms of a peace agreement hammered out years before is a cause for celebration not least because of the way it demonstrates that civil wars, even wars that have endured for decades, can be settled by political processes. Some observers will have been surprised that the referendum was held at all; many will be amazed that it was help exactly on time, in accordance with the CPA. Not that it’s all sorted yet.

The Referendum is the mechanism that puts into effect the right to self-determination but once the decision to secede has been made and accepted by all sides, there will be months and even years of arguments and negotiation over a string of key issues that have not yet been resolved….such as the boundary between northern and southern Sudan, the future of a contested region that was not included in the Referendum, and perhaps most critically, financial issues such as the division of the debts which Sudan owes and the division of the income from the oil which is Sudan’s most important export.

The ultimate success of the peace process, of which the Referendum is but one key ingredient, will be shaped by the outcome of these outstanding issues.

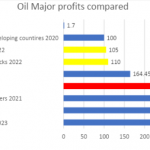

One thing that will not change is the importance of oil to both Northern and Southern Sudan. Sudan’s oil reserves lie largely in the South – but refining and shipping capacity is almost exclusively located in the north. Sustaining the oil economy is in the interests of both governments – means that whatever the outcome of the Referendum, there will be a high level of interdependence between the two Sudan’s for the foreseeable future.

This inter-dependence has the potential to confound simplistic analysis and policy responses. Sudan has had a problematic and distrustful relationship, with western governments at least, for many years – illustrated for example by its readiness to give refuge in the 1990’s to ‘Carlos the Jackal’ and Osama bin Laden, two of the world’s most wanted fugitives for terrorist activities, the decision by President Clinton to bomb a pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum and more recently, the indictment issued by the International Criminal Court against the current President for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in relation to the civil war in Darfur. It will be interesting to see if these distrustful and antagonistic relations continue in the future. One possibility is that a more accommodating tone will become more of a feature of the relations between Northern Sudan and western governments as part of a strategy to encourage the government of Northern Sudan to accept secession and resolve the outstanding issues for negotiation. What such a change of tone might mean for the peoples of Darfur or the eastern regions of Sudan will be something to watch.

As for Southern Sudan, the new government will face quite extraordinary challenges. Southern Sudan is vast, has very little infrastructure – such as schools, medical fa cities and transport – and suffers the consequences of decades of war, displacement and economic marginalisation. In stark contrast, the expectations of its peoples will be immense. Managing these expectations and inspiring its peoples with a vision for the kind of society to which they aspire at the same time as conducting complex negotiations with the government of Northen Sudan will be a delicate balancing act.

Ian Leggett is former East & Central Africa Regional Manager for Oxfam, and former director of People & Planet.

Though they will have a significant interdependence for some time to come, the cards may well be in Sudan’s hands. There seems to be too much stress on the “proven” oil fields and little acknowledgment for the potentiality of oil in the North, particularly in Darfur. This may be a significant mistake, as though South Sudan may be off on their own at some point, all of the oil so far drawn has come entirely from the shared “proven” fields.

http://www.mohammadmufti.com/2011/01/some-reflection-on-upcoming-division-of.html