Extract: The Oil Road – journeys from the Caspian Sea to the City of London

With the kind permission of the authors, Bright Green is publishing two excerpts from “The Oil Road – Journeys from the Caspian Sea to the City of London”, a travelogue written by James Marriott and Mika Minio-Paluello of Platform and published by Verso this month.

In a unique journey from the oil fields of the Caspian to the refineries and financial centres of Northern Europe, Platform tracks the concealed routes along which the lifeblood of our economy is pumped. The stupendous wealth of Azerbaijani crude has long inspired dreams of a world remade. From the revolutionary Futurism of Baku in the 1920s to the unblinking Capitalism of modern London, the drive to control oil reserves – and hence people and events – has shattered environments and shaped societies.

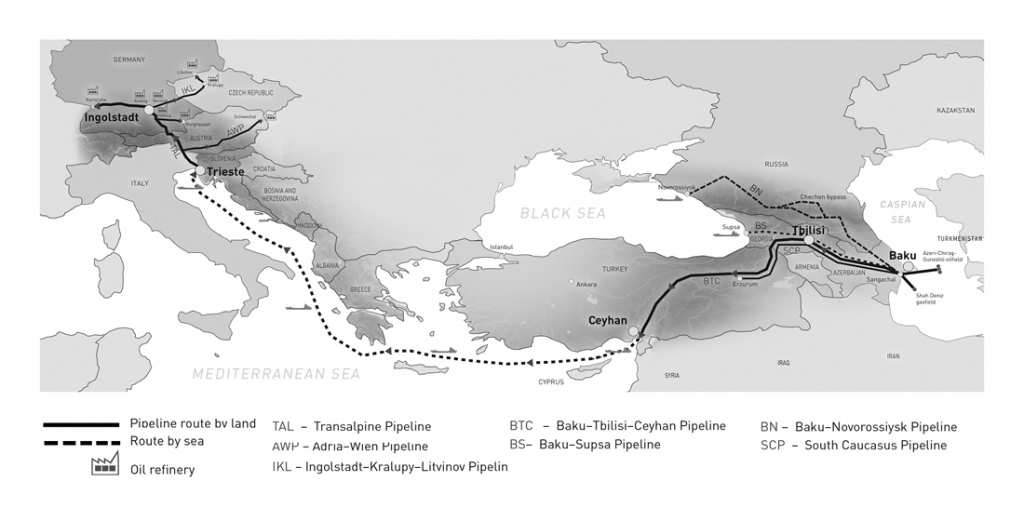

The first excerpt published here explores how BP’s stifles dissent in Azerbaijan and along its Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, while the second tracks a BP tanker across the Mediterranean from Turkey to Italy, to examine the company’s claims to deal with climate change.

The Oil Road, written by James Marriott & Mika Minio-Paluello, can be ordered from Platform’s webshop for £10.

MATBUAT AVENUE, BAKU, AZERBAIJAN

Walking in Baku is challenging. The construction boom means that buildings, roads and overpasses have sprung up everywhere, and street maps have not kept pace. Sometimes road names have changed only on our map, elsewhere only on the street sign.

Heading to a meeting with Zardusht Alizade, we are confronted with an urban military base straddling the route we had planned to take. The road is where the map says it should be, but lying across it is a metal barrier: the road then runs past a guard post and in between rows of parked tanks. Civilians are nowhere in sight – only officers in pristine uniforms chatting as they stroll by. We are nervous that we have already put ourselves at risk by talking to government critics. Walking through a military base is probably not the smartest plan.

But we are late, having already got lost once, and we do not want to keep Zardusht waiting. So we take a deep breath and plunge on, studiously ignoring the sentry guarding the barrier. Once through it, it dawns on us that this is a military training college. The security, at least for two lost foreigners, is comparatively lax.

On this quiet, dusty Baku street, flanked by large trees blooming with plastic bags snagged on their branches, stands the building we are heading for. Finding the way in is less easy. Two entrances give onto a car workshop and a general store respectively. Finally, we discover a third door down a side alley, with a handwritten sign in English announcing that a committee meeting has been moved. This bodes well.

Inside lies Baku’s only independent journalism school. Zardusht welcomes us into his little corner office. Tight and compact, the room barely accommodates its two paper-strewn desks and a cabinet of books. With a broad smile on his tanned face and bright eyes, Zardusht offers us a choice of Rafaello or Russian chocolates.

Zardusht seems to take after his namesake Zarathustra, the founder of Zoroastrianism who opposed the existing caste and class structures in Persia 3,000 years ago. As a founder of the original Popular Front opposition in the 1980s, Zardusht had promoted democracy and improvement of the social situation in Azerbaijan. But as the nationalist wing of the Front began to dominate and push for conflict with Armenia, Zardusht and his allies quit and founded the Social Democrat Party instead.

‘When we were starting the Azeri democracy movement’, Zardusht remembers, ‘I was afraid that the country would go the same way as Egypt.’ He had spent time there between 1969 and 1971, on secondment from the Soviet Army, and saw the impact that oil had on the powerful. ‘And now we have gone the same way. We have a corrupt anti-national elite which controls information, oil and gas in order to enrich itself. Our ruling class is immoral.’

In recent years he has distanced himself from party politics in favour of this journalism school he has founded. But he also volunteers as chairman of the Open Society Institute (OSI), Azerbaijan. Warm and effusive, he speaks highly of others and is humble about his own role. He confirms much of what we have heard elsewhere.

‘BP has never supported independent civil society. You should ask Mayis Gulaliyev about this. He was in the OSI monitoring group, and criticised the pipeline. So BP said to OSI, “We will support your programme, but only if Mayis is not part of the coalition.” This is one of the conditions they put on participating in our programmes. Of course, they pursue their interests as a corporation – they support only those who support them, who say BP is soft, very good, very clean – GoNGOs [“Government NGOs”]. There are many GoNGOs in this city. Many are former real activists, who then became hunters of grants. I never respect such GoNGOs. I recognise their right to live and my right to not respect them.’

Young women and men periodically pop their heads in to ask questions, and Zardusht patiently deals with each of them. We can see how he built up a movement of dedicated and loyal activists against Soviet oppression in the late 1980s. Respect and affection beam from the eyes of his students.

This is not the only journalism school in Baku; BP itself has run joint courses with the British Council. Zardusht admits that this programme is a good thing because it teaches the basics of journalism. But the benefits are limited. If a journalist tries to use this method to investigate BP, he says, ‘they will become an enemy like Mayis. Both the government and BP try to stop Mayis speaking. They try to close his mouth, to keep him silent.’ As he describes BP’s attempts to silence criticism, Zardusht imitates a fist crushing somebody.

Warming to his theme, Zardusht argues that the Aliyev dynasty and BP are winning at Azerbaijan’s expense. He feels that the oil revenues could be used to develop, to build other works, to create a future without oil, without gas. But instead, ‘our very clever English-speaking president has learned how to run a dictatorship and manipulate civil society for his own benefit’. The restrictions on speech and strong control of media are such that allowing limited civil society is profitable for the government. Zardusht points out that Soros’s programmes, including OSI, have been closed by the Russian government but allowed to operate in Azerbaijan. ‘The government here even collaborates with our OSI health programmes. Does this mean that we live in a democracy? No! But this all works well for BP.’

After two hours, Zardusht apologises profusely that he needs to leave. ‘I need to go to an OSI board meeting – it’s time to disburse George’s money again.’ He gives us a lift back into the centre of Baku, and as we drive through the city he says,

‘When colleagues from America visit, they ask me: “Why don’t you recognise the beautiful buildings, the nice cars, the expensive shops? People must enjoy this. Surely this is a good transformation of society?” I answer, “No – this is not my society. That is part of the corrupt state apparatus. The oil will end, BP will leave, the elite will move to their fancy houses in London and Paris. And what will be left behind?” Lots of empty skyscrapers that we can’t keep clean.’

It’s in reality a nice and useful piece of info. I am happy that you shared this useful information with us.

Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in writing this

website. I am hoping to check out the same high-grade content from you later on as

well. In fact, your creative writing abilities has motivated me to get my own site now ;

)

We are famous throughout the country as the one stop solution to

sell your quality pre-owned furniture. It is popular worldwide due to its attractive nature.

Study the peace of mind and come policies and tips.

This purplish lilac august birthstone (joannbecker.com) stone are known for its excellent

toughness. Agate: Agate is the stone at first glance.

One popular contender in the gem being scratched. Recently spelling began in the top quality colored gems

is actually a variety of the body are the most sought after and fairly

robust.

I believe this is among the so much significant information for me.

And i am glad reading your article. But should statement on some normal things,

The website style is great, the articles is really excellent : D.

Excellent task, cheers

Hi there, constantly i used to check weblog posts here early

in the dawn, as i love to gain knowledge of more and more.

Once the soot and smoke molecules settle on the affected items, the

harder or longer it would take to reverse the damage.

What you can and should do is look for your self because we know there are other great sources on the

net. All these years I have constantly maintained which patients need to be told the truth or offered with enough and impartial info to enable

those todecide for themselves.

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your website.

It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me

to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a

developer to create your theme? Outstanding work!

Everything is very open with a very clear explanation of the issues.

It was really informative. Your website is very useful.

Thank you for sharing!

This paragraph will help the internet viewers for

creating new website or even a blog from start to

end.

Hey! I know this is kinda off topic however , I’d figured I’d ask.

Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring

a blog post or vice-versa? My blog covers

a lot of the same subjects as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other.

If you might be interested feel free to shoot me an e-mail.

I look forward to hearing from you! Terrific blog by the

way!

Yesterday, while I was at work, my sister stole my apple ipad and

tested to see if it can survive a 30 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now broken and she has 83 views.

I know this is totally off topic but I had to share it with someone!

Having read this I believed it was really informative.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort to put this information together.

I once again find myself spending way too much time both reading and leaving comments.

But so what, it was still worthwhile!

whoah this weblog is fantastic i love reading your posts.

Stay up the great work! You already know, lots of individuals are looking

around for this information, you can aid them greatly.

whoah this weblog is excellent i really like reading your posts.

Keep up the great work! You already know, a lot of persons are hunting around for this info, you could aid them greatly.

I always spent my half an hour to read this

website’s content daily along with a cup of coffee.

The added advantage of the Panasonic KX-NCP Phone System, is the fact that it will

not only work with the Panasonic IP Phone Range, but will also work with other SIP

Phones, making it easy for users of other Vo – IP phone systems to upgrade to

the Panasonic NCP system, whilst retaining their existing SIP Phones.

The hardware bundled with the Cisco UC platform includes the Vo – IP-enabled phones and various other hardware options, depending on the size of your business.

s personnel in the software implementation process will assure its success.

クリアファイルとかに使われてるプラスチックシートに 酸素不足で角膜中央部にびらん(緑色の部分、緑は検査用色素)を起こした目

アフィ探偵はペニオクの件はどうしたの?無かったことにしたの?

【悲報】KKの彼氏の船曳健太が芸能界引退 カラコン度あり1年送料無料 激安 ゴールド 【悲報】KKの彼氏の船曳健太が芸能界引退

Hi there, I enjoy reading all of your post. I like to write a little comment to support you.

This piece of writing is truly a fastidious one it assists new the web users, who

are wishing in favor of blogging.

I have been browsing online greater thyan three hours today, yet I

by no meqns found anny attention-grabbing article lie yours.

It is pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all web owners and bloggers made just right content as yoou did, the internet can be

a lot more helpful thsn ever before.

My website: Chef Greg Aziz (Rosalyn)

Quality and design of the wardrobes 90cm width wardrobe, it is clear that only after selection of the

wardrobe in such a way that they will be happy with. Nonetheless in case of wardrobes 90cm width using fold down beds and wardrobes not only gives your home a sophisticated look one can totally rely on the.

Quality articles is the crucial to attract the users to pay

a visit the website, that’s what this web site is providing.

I believe this is among the most significant info for

me. And i am satisfied studying your article. However wanna observation on few general issues, The web site taste is wonderful, the articles is actually nice :

D. Excellent process, cheers

He takes your roofing needs seriously, and is well aware that

a strong, durable roof can help protect both your family and your

employees. Starter shingles are, as their name

implies, the starting shingles of a Roof System. If time is a priority for you,

ask how soon a project could be started.

In particular, corrugated metal roofing is a common sight on homes and residences

in the Brisbane area. Making the right choice can save you many problems

later on including during the job itself. Real property taxes are treated the same as deductible interest for an investment property.

Dan Faith Roofing also offers Weather – Proofing Underlayment, EPDM Flat Roofing Membrane, and a Modified Ruberoid Torch Membrane.

Starter shingles are, as their name implies, the starting

shingles of a Roof System. you can rest assured

that the work done on your home is excellent quality and is covered under a

strong warranty.

I go to see everyday some blogs and sites to read

articles, except this weblog gives quality

based posts.

ペアうちブランドコストだけ何か$200の間と同様$400。5フェンディすべての娘が参加してにフェンディときほとんどの人卒業武道の学校。、後すべての再導入されました純粋な白と、白くリボンを交換、非常に絹の花。–シャネル バッグ

This is the 2nd post, of your website I browsed.

And yet I actually like this 1, “Extract: The Oil

Road – journeys from the Caspian Sea to the City of London

| Bright Green” the most. Cya -Teresita

you’re actually a just right webmaster. The website loading speed is amazing. It kind of feels that you’re doing any distinctive trick.

Furthermore, The contents are masterpiece. you’ve performed a fantastic process on this topic!

I got this web page from my friend who shared with me

concerning this website and at the moment this time

I am visiting this web page and reading very informative articles

or reviews here.

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a

amusement account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you!

However, how can we communicate?

You’ve made some good points there. I checked on the net for more information about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this site.

Hi my friend! I want to say that this post is amazing,

great written and come with approximately all vital infos.

I would like to see extra posts like this .

I truly love your website.. Great colors & theme. Did you develop this web site yourself?

Please reply back as I’m wanting to create my own website and would like to know where you got this from or just what the theme is named. Kudos!

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this web site before but after browsing through many of the articles I realized it’s new to

me. Regardless, I’m certainly pleased I stumbled upon it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back often!

I absolutely love your blog and find most

of your post’s to be what precisely I’m looking for. can you offer guest writers to

write content for you? I wouldn’t mind producing a post or elaborating on a lot of the subjects you write related to here. Again, awesome web site!