Nelson Mandela: see the movement he personified as well as the great man

There’s not much that anyone can add to the massive outpouring of grief and admiration for Nelson Mandela. His status as the greatest secular saint of our era becomes clearer as everyone from the Pope to those who campaigned to have Madiba hanged in the 1980s come out to talk of his great life and his great legacy.

The peaceful transition to democracy, the quelling of tribal tensions and the re-incorporation of South Africa into the world economy were all massive achievements that should not be underestimated. But the failure to secure economic freedom and democracy for South Africans remains Mandela’s greatest oversight.

There has been plenty of comment on the attempts to de-politicise Mandela, to brush over his past as a soldier, freedom fighter and friend of Fidel Castro. It’s important that we resist this form of de-politicisation of the greatest figure of our age.

But there is something we must understand about the life and politics of Nelson Mandela. While Nelson Mandela personified the struggle against apartheid the struggle was much, much more than that of one man.

Some will try to claim that through one man’s personal sacrifice, personal magnetism and great ability to forgive those who wronged him apartheid was brought crashing. This is a dangerous story and one Mandela himself rejected.

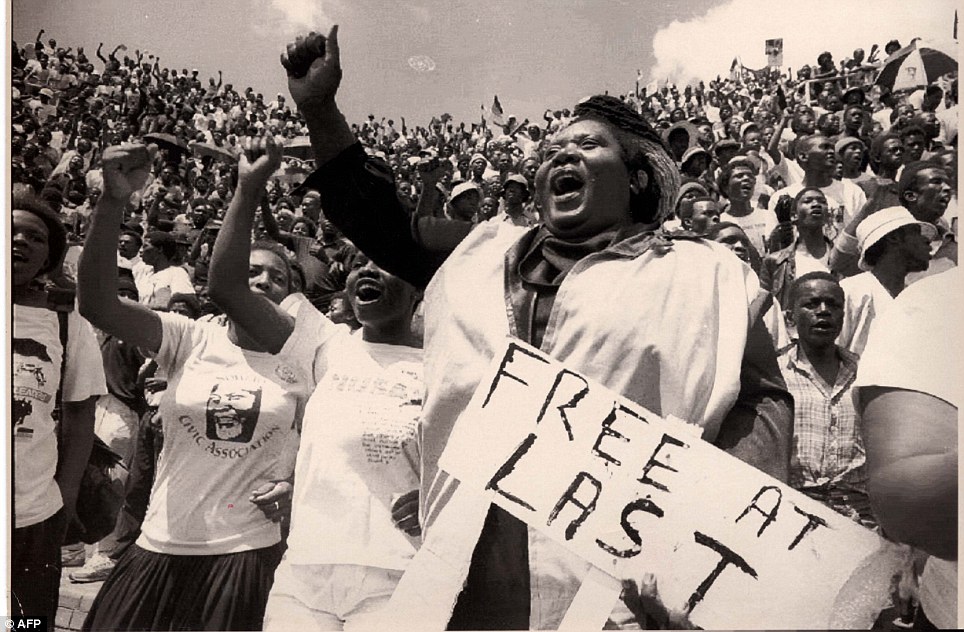

Not only was the ANC more than one man, it was itself part of a wider liberation movement (the United Democratic Front), which brought together all the significant elements opposed to apartheid. But much more importantly it was a mass movement that toppled apartheid. The UDF comprised over 400 groups from churches, youth movement, political parties and workers’ organisations committed to ending apartheid.

From the Soweto uprising in 1976 that made Steve Biko famous to the mass action campaigns of the 1980s, it was mass civil action that drove the apartheid regime to the negotiating table. This movement, comprising huge numbers of ordinary people was the movement that Mandela came to personify.

But as time has passed, and the economic settlement accepted by Mandela’s Finance Minster and successor as President, Thabo Mbeki has failed to deliver economic freedom, the legacy of the mass movement is barely remembered. And the lessons of its failure are ones we should learn.

The mass movement worked because it had both massive popular support, with the ability to put tens of thousands on the street and a political expression through the ANC. When buttressed to the tripartite alliance of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), South African Communist Party and ANC the liberation movement was lively and diverse.

The failure of the mass movement was to come after the first democratic elections, where having achieved political freedom, too much trust was placed in the formal structures of COSATU and the ANC. This allowed too much power to rest with government. What was needed was for the popular front and mass movement to continue the struggle for economic freedom.

While Mandela and Mbeki were being talked into continuing elite control of the economy, the need for a popular movement was as important as ever. As South Africa continues to struggle with the challenge of creating an economy for all, the failures of the government under Mandela become clearer.

Of course, this comment is most easily made with hindsight. At the time when the ANC took power, the left was in disarray following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the case for socialising the economy was at its weakest in the twentieth century. To understand why the Mandela government failed to democratise the economy is, though, not to condone it.

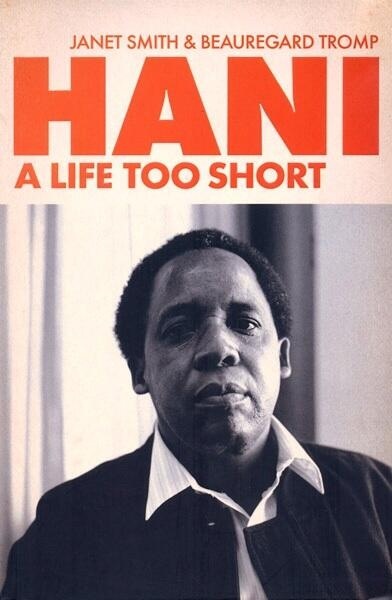

One of the quite correct criticisms of the drive to depoliticise Nelson Mandela is that it underestimates the role of others in the struggle. Oliver Tambo, who led the ANC in exile, Walter Sisulu, who had recruited Mandela to the ANC and Chris Hani, who was second only to Mandela in popularity, having been commander of the ANC’s armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe in exile.

Nelson Mandela with Chris Hani

Had Chris Hani not been murdered on the orders of a Conservative MP in 1993, we may have had a continuing mass movement that could demand universal, free health, land ownership and full economic democracy. Hani said before his death:

“The perks of a new government are not really appealing to me. Everybody, of course, would like to have a good job, a good salary, and that sort of thing. But for me, that is not the be-all of a struggle. What is important is the continuation of the struggle – and we must accept that the struggle is always continuing – under different conditions, whether within parliament or outside parliament, we shall begin to tackle the real problems of the country. And the real problems of the country are not whether one is in cabinet, or a key minister, but what we do for social upliftment of the working masses of our people.”

If Hani had lived many believe he would have been President, and a statesman to compare with Mandela. But he may not have taken that path, he may have created a movement to oppose the moneyed interests who still control much of South Africa’s wealth.

Mandela was a great man, he led a great movement for political freedom. He was a radical, who stood with the oppressed in his own country and around the world. But his achievements were in no small part due to the mass movement that drove the apartheid regime to the negotiating table. What we need is not more leaders like Mandela, but more mass movements which create social, economic and political change. Those movements may create people like Nelson Mandela, but more importantly they can create the world that we want and the world that we need.

The struggle continues!

Great web site, been looking forever for ideas on the

very best rattan furniture pieces for our home and in our garden. This site truly helpedgreat blog some great info here

My page; rattan garden furniture (http://portroyalrattan.over-blog.com)

Was in actual fact searching for just a traditional shower

enclosures when I uncovered this web site, didn’t even know there was such a thing as a ‘steam shower enclosure’, wow, may just have to acquire one

Feel free to visit my web page :: steam shower generator (youtube.com)

best gaming laptops

A good article.

When I was in South Africa earlier this year, lots of people in the present day social movements said that they respected the great man, but that the global focus on him distracted both from present day social movements and the struggle that continues post 1994.

I hope this moment can inspire us to build solidarity with the ongoing struggle for economic justice in teh country.

I think you’re right to highlight this – the struggle was not just one man and much of what happened would probably still have happened had he never existed.

There is a certain amount of the Ghandi effect to this. After India achieved independence the British state bestowed on Ghandi a kind of historical “official opposition” status in part to write out of history many of the communist and/or armed elements that were also fundamental to the withdrawal of British colonial rule.

So both Ghandi and Mandela become nice old men who somehow won justice through smiling politely and tutting with a chuckle now and then. You can see why they might prefer people to think this is the only effective way to achieve things. Of course with Mandela this requires a certain amount of rewriting of history.

I think the more charitable reason is that actually many of the elements that make up the ANC are murderers, thieves and corrupt officials who are definitely part of the problem not the solution. Decoupling Mandela from his own organisation is a way of avoiding a more complex debate (I think justifiably to some extent) and focusing on the positives.

One last thing. There is also a specific contribution that Mandela made, and on the occasion of his death I think it’s right we remember it. He prevented a civil war in which tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of his own people would have been killed. That means something real I think, and had others in the ANC been in his position in 1990 the outcome could have been very different.