What we’re saying Yes to: utopian, regenerative projects like Grow Heathrow

The following article is part of a series on Bright Green, What We’re Saying Yes To, inspired by Naomi Klein’s recent book, No Is Not Enough. More contributions welcome at: front-desk@project1-hvznj9e2s8.live-website.com

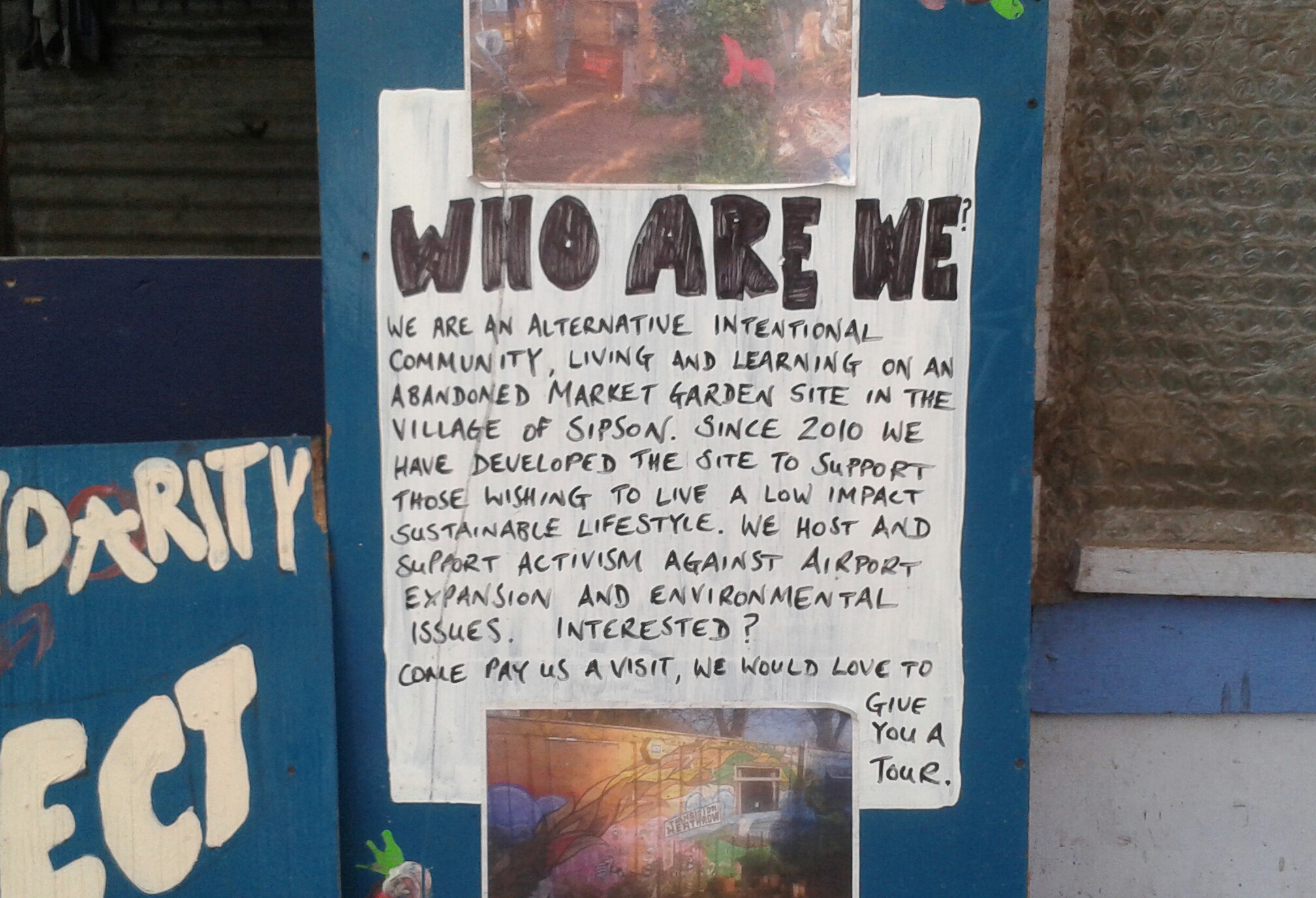

In a small, unassuming village in the west of London, nestled in a corner of the M4, is a radical experiment in doing something different. In amongst the peaceful, genteel streets of this suburban environment are a motley crew of radicals trying to halt a third Heathrow runway by building something wonderful and beautiful in its place. That place is called Grow Heathrow.

The best way of summing it up is this: it was originally set up as a permanent protest camp against the proposed third runway at Heathrow Airport, but has now evolved into a permanent experiment in sustainable living. Living on squatted land, cleared and transformed out of a derelict market garden in 2010, there are around 20 – 30 long-term volunteer-residents. It emerged out of the legacy of Climate Camp – the (in)famous direct action climate group – and the blossoming Transition Town movement.

To be clear: they are not proposing back-to-the-land as a long-term, realistic solution to the climate crisis. (Well-insulated housing with energy coming from 100% renewables is a real long-term solution.) No: it is merely an experiment, a hub, an alternative space where people can explore possibilities. They operate on co-operative principles of consensus and equality, with an effort to be as inclusive of marginalized groups as possible. Day-to-day life involves workshops, bicycle maintenance, community meals, talks, and many swims in the local lake – all while getting by on odd jobs and freeganism.

As for Heathrow. Even the name itself is evocative of that flutter-in-the-chest, exhilarating excitement about the possibilities of reaching out into the world. I recall as a kid watching Airport on TV, dreaming of the exotic locations people would go to, hoping one day to follow them. For the record, I think it’s very important that Britain is connected to the world economically, socially and politically. I don’t support a third runway – but I’m not sure I support zero runways either.

But as ever in life, it’s about balance. Heathrow currently processes just over 75 million passengers a year – the equivalent of every citizen in the UK, and some. Indeed, our GDP is currently just over $40,000 per capita. Perhaps we’re connected enough already. Perhaps we’re rich enough already – albeit with a very real and very grotesque problem of unequal distribution. At Grow, they are developing new ideas of what prosperity and connection mean.

Officially, UK aviation contributes around 6 per cent of greenhouse emissions – but this is widely regarded as a significant underestimate once you factor in aviation multipliers. The additional GHGs from the additional capacity would be the equivalent to that produced by whole economy of Kenya. The business case for Heathrow 3 is bogus: business flights are in long-term decline. With a third runway, the number of flights per year is expected to increase from 480 thousand to 700 thousand per year: an enormous increase. Think of the polluted hell’s mouth that London can be already: imagine what it would be like with a jump like that. It’s madness.

Climate change, however, is far from the only environmental issue, and it’s at places like Grow where you are provoked to wonder what “environmental crisis” actually means. It’s more than just the noise pollution and the air pollution: I wonder, sometimes, if it’s reasonable to describe human disconnection from the natural world as an example of environmental crisis – an excess of grey space, and a lack of green space. People living in London need some space to breathe again. At Grow, they’re helping to create that space.

I have long been drawn to this place, ever since I heard about it during the student movement of 2011. I have always had this amorphous feeling of being lost in life, of finding ordinary life in a market-driven economy impossible and difficult and deeply unpleasant. If you want to have a decent, safe place in ordinary society, you need to have money and certificates and positions. But at Grow, they work towards an atmosphere of egalitarianism and inclusivity. You contribute, in whatever small ways you can, and you feel valued. Ordinary life, with its hierarchies and external signs of success and failure, creates these feelings of exclusion. People are disposable. The earth is disposable. All part of the throw-away culture. But not at Grow – who embrace the circular economy, “humanure” and all.

I often describe it in two words – revolutionary and regenerative. Revolutionary because its mere existence, existing on squatted land, challenges the logic of capitalism itself – the owners, with no rent-payments or lease-holding, aren’t getting any return on their assets. (The scarcity of space and housing today is an artificial scarcity, as Marx observed.)

And I call it regenerative because it’s about building, growing and developing something in place of our market-driven world, where people and the earth are de-commodified. For me, ultimately, it’s about reclaiming and recreating the commons. It’s socialism from below. As John Holloway writes in his book Crack Capitalism: “Break [capitalism] in as many ways as we can and try to expand and multiply cracks and promote their confluence.”

Of course, there will be those who regard such a project as squalid and horrible. But filling London’s air with toxic, noxious fumes is squalid and horrible. Privatising England’s water systems is squalid and horrible. Leaving the legs of oil rigs to decompose in the already-suffering seas is squalid and horrible. Failing to recycle is squalid and horrible. Taking countless flights abroad is squalid and horrible. Our elites are filthy rich, quite literally.

To what extent is such a project powerful? When you think about the smooth operators of the corporate class, with their lobbyists and PR campaigns, does a rag-tag army have much of a chance? Honestly, I don’t know. Any power it gets is part of a wider campaign with the local community – who mostly back them. Moreover, I find myself thinking of a quote in Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything, “Love will save this place”. If there weren’t communities there to protect, I don’t think I would care half as much. These communities can pack a punch when they’re well organised: Boris Johnson, no eco-warrior, opposes it outright, no doubt due to the strength of the local Uxbridge community which he represents. The aviation executives themselves are not confident of movement in the next 10 years. The government has given the green light, but the parliamentary vote is yet to come, which, with such a slender government majority, is all to play for.

Perhaps it’s wrong to romanticise it. Living there is probably tough and difficult at times. Residents, I am sure, will have their disagreements and arguments – and I’m sure many miss the ordinary comforts of home life. Winter doesn’t sound pleasant either, nor even the intense summer heat. Still sceptical, though? Take my advice, go visit in the height of summer, and take one glorious dip in the nearby Saxon lake, and enjoy being part of an oasis of sanity in an insane world.

THe need for a 3rd runway at Heathrow is not necessary!! The RE is an almost perfectly suitable site nearby wicht already hans 2 runways that is the old London AirPort at Northholt now under User by the RAF while only at present suitable for smaller OR sporter take off aircraft thuis Many slots at Heathrow could be moed & thuis site User releaving the RAF opsomde unnecessary Costa & the museum Mignon het Many more visitors , iT is so near Heathrow that iT would-be be possible to transfer from 1 to the other easily & save vast Costa & environemental damage!! I have Said thuis for Some years but with little response so far, WHY?? Ï Please excuse Amy errond as I can hardly see what I am typing.