Mixed fortunes – Global Green news round up issue 1

A lot happened in 2018. From the huge anti-corruption protests in Romania, to a first free elections since the 80s in Zimbabwe. From Columbian elections to Malaysians ousting the party that has ruled since independence. As we settle firmly into 2019, it is crucial to see the trends, the victories, the mistakes. Did political ecology make some important gains, or does it seem further away than ever?

Come with me as we revisit some of 2018’s most notable events…

Italy

March’s election saw the creation of a far-right populist government. Echoing a Europe-wide decline of traditional parties, Italy’s new government is formed of small, relatively new parties. Namely, the far-right party the Lega and populist ‘Five Star Movement’.

In these elections, the Italian Green Party (known as the Federation of Italy Greens or FDV) were part of a list ‘Italy, Europe, Together’ with the socialist party and others. This list gained 0,6% and the two people elected were not Greens but socialists.

Whilst Italian environmentalism has grown, its political party incarnation has struggled. It has had a tumultuous decade, gaining then losing high-profile voices, and being struck by the ‘perfect storm’ in 2007-2008. However it has incubated one of Europe’s leading Green voices – European Green Party co-chair Monica Frassoni. She hopes that the recent ‘Green Wave’ can reach Italy in the European elections in May 2019. Greens are already preparing a list – centred around environmentalism, an open society, and feminism – which brings together diverse political parties and civil society.

One key thing to take away from these elections is Facebook’s amplified role in politics. This was showcased by the new deputy prime ministers – Matteo Salvini from the Lega and Luigi Di Maio from the Five Star Movement. They each garnered 7.8 million likes and shares in two months alone. The current hostility and downright racism of their administration – turning away boats of rescued refugees, treating migrants like criminals – reflects an international shift to the right under ‘strongmen’ such as Viktor Orbán in Hungary.

Spain

Valiantly countering that trend was Spain. June saw its longstanding right-wing government, headed by the Popular Party’s Mariano Rajoy, succumb to a vote of no-confidence by Spain’s socialist party, the PSOE. Pedro Sánchez took over as Spain’s new Prime Minister, unrolling in his wake the most female-dominated cabinet in history. Spain’s Green Party EQUO has modest but important representation in Spain’s parliament and at the European level. They have been key in supporting the new government’s more humane attitude to migrants and asylum seekers and the green measures implemented by the new government – such as a ‘just transition’.

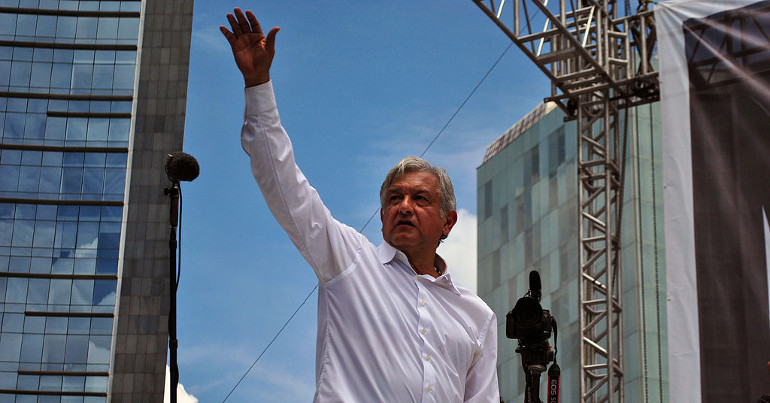

Mexico

Clearly Hispanic countries are pioneering shifts to the Left – as Mexico elected President Lopez Obrador (also known as AMLO) in July. Previously Mayor of Mexico City but a political outsider in many ways, he stood on a platform of redistribution, corruption overhaul, and a new approach to gang violence.

Since taking office, he has halted plans for a new airport and champions its first female mayor who is an environmental scientist. But proposed cuts to the Environment Ministry’s budget and his plans to re-nationalise Mexico’s oil companies and ramp up extraction put paid to hope that he would be a ‘Green’ president. Mexico’s ‘Green’ Party – deemed by many to be ‘Green’ in name only because of its stance on issues like capital punishment and gay rights – may not be the place to look for inspiration.

Brazil

Months later, political upheaval engulfed another Latin American big player, as Bolsonaro was elected as President in Brazil amidst unprecedented public opposition.

Latin America’s first ‘Strongman’, Bolsonaro’s comments about gay people, women and indigenous people make Trump look almost moderate. On the Amazon rainforest he is ruthless, planning to ramp up destruction. In a country still reeling from the murder of activist Marielle Franco in March, his comments romanticising Brazil’s military dictatorship and calling for more police powers has rung alarm bells. Brazil’s environmental movement, including two Green Parties, faces a tough political climate.

Green wave

In one glorious mid-october weekend, the Green Parties of Luxembourg, Belgium and Bavaria (Germany) shot up to percentages and power as yet unheard of. The Luxembourg Greens increased their MPs by 50% and are now in coalition – with the country recently announcing free public transport by 2020. Belgium saw its Greens coming second if not first in many towns and cities, especially in Brussels. In Bavaria the pro-refugee, Leftist, and radically environmental Greens overtook the Social Democrats to come second with 30% of the vote, ending the domination of Bavarian government by the CSU (the CDU’s sister party). Greens in nearby Hesse also did historically well soon after.

What does all this mean?

Was this wave assisted by the recent release of the IPCC’s report on the urgency of climate change? And what do we make of how this Green wave happened in Europe’s wealthiest nations, those least hit by austerity and the refugee crisis?

Whilst Italy showcases two global trends – social media’s increasing political clout and the rise of authoritarian ‘strongmen’, Bavaria displays two others. The first? A tangible global fury at the lack of action on climate change, erupting through mass demonstrations or Green votes. Second: a backlash against insular and xenophobic politics powered by fear. Bavarians liked the Greens’ bold and honest stand on these issues – even though their positions were considered political suicide by other parties. This tells us that Greens must stay true to their principles – albeit strategically – and can shape the political agenda.

Considering Central Europe – Hungary and Poland particularly – moving in the opposite direction, away from European unity and into fear of the other and authoritarianism, will geography be a new faultline? Does this herald, as Ivan Krastev asks, the re-emergence of an old European division: not between Left and Right, rich or poor, but between East and West?

There is much we don’t know. What is certain is that 2019 holds important elections and the coming into 2018’s new world leaders, constrained or supported by an array of movements and organisations, local to international. The European elections may well lead to a complete reconfiguration of the parliament, with the Greens/EFA having to make new alliances. Will Canada have its own Green wave in October? India will have a general election. And Thailand, Slovakia, Finland, Israel and many more – I’ll keep you up to date

Things have changed in a world where just ten years ago international institutions ruled and globalisation seemed unstoppable. A global financial crash later, it seems the nation state is back with a vengeance, as John Bew puts it. Yet our problems – and their solutions – are not contained to arbitrary national borders. Internationalism is key to the environmental and social justice. It challenges the inward-looking, closed attitude that prevents real change and that movements across the political spectrum have retreated into. But whilst things may look bleak, political ecology gained ground – not only in Rwanda, Germany, Belgium… but in people’s minds. In France and Britain, the Greens were the most well liked party (not that the competition was too stiff)… So why not end with the victorious Bavarian Greens’ campaign slogan ‘Rather than spread fear, give courage.’

Thanks for an informative piece. It finishes well – ‘Rather than spread fear, give courage.’ Let us all live up to that.