Telling the history of migration is an important step in establishing safe routes for refugees

Last week, with the world’s attention focused on the climate talks in Glasgow, there was yet more tragedy, desperate danger and awful fear in the Channel. At least four refugees drowned, many had to be rescued, and hundreds more crossed one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes in flimsy, inadequate little boats.

From the right wing, came the inevitable attacks on the French for not stopping the flow of desperate people, despite all the evidence, over so many years, in so many parts of the world, that when one route is blocked, desperate, ingenious people, who’ve already survived impossible journeys, will simply find another, each inevitably more dangerous than the last.

The origin and destination states change, often reverse, but the pattern is the same. A century or so ago, it was people fleeing persecution, political repression, seeking a different life, who flooded in their millions out of Europe.

In a humble London suburban shopping centre, beside the usual chain stores, with a brilliant market just outside the door, is the current home of the Migration Museum, which tells some of their stories, as well as the stories of today.

It is a far cry from the migration museums that I have visited elsewhere in Europe, in a grand historic building in Paris, in a high-tech, obviously well-funded refurbished port building in Hamburg. Like London’s, they’re part of a global network of more than 80 institutions that together research and explain to their communities and visitors the often shifting nature of human existence. (New York has two: the famous Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration and the brilliant Tenement Museum.)

In a way, the Lewisham location for the UK institution is fitting: the museum is at the centre of a flourishing multicultural community, with a wonderful range of foods and clothing, experiences and knowledge right on its doorstep. And the richness of its displays, from the diverse accounts of one of the largest movements of people in human history, Britons spreading around the world (including, amazingly, Welsh communities in South America that still maintain their original lingua franca), depicted in its current Departures exhibition to its “acutely personal and immersive exhibition” (as The Hindu reported it) telling the stories of recent arrivals to Britain through the objects they chose to bring with them, and the taste of both homes they blended.

But still, this is a temporary location for the museum. It has no regular government funding, having had to cobble together income from a wide variety of sources using the ingenuity of staff and trustees – using not quite a begging bowl, but something very like one. It would also love to take this community outreach model – ideally from a stable base – and spread it around the United Kingdom.

That was an issue I raised in Oral Questions in the House of Lords last week, and was pleased to have a high level of engagement – slots being heavily oversubscribed when so many OQs at present are the opposite.

As I said then, the government talks about building the “Global Britain” brand: well surely it should be providing stable, secure funding for a permanent, established structure and an accompanying research and education programme? That could be a sign that the UK is a nation comfortable with its complex international history and current roles.

Education would be a particular focus, given that, as crossbencher Baroness Whittaker raised, a recent study by the Petitions Committee in the House of Commons found that teachers find the subject “difficult”, and would greatly appreciate help in covering this part of the curriculum. That’s a natural role for a museum – and the Migration Museum already provides some great online resources and materials, and as many visits as possible in its limited space – but with more resources, and a higher profile, it could do a lot more.

It isn’t only pupils who could benefit. The Windrush Lessons Learned Review concluded that the Home Office should do more to inform its staff about Britain’s colonial history and migration links – and engage more with immigrant communities, something for which the Migration Museum would be a natural conduit, as Labour’s Baroness Hayter of Kentish Town referred to. The Museum already does this for the Home Office and other government teams, and organisations such as the Metropolitan Police, but with more funding it could do far more.

The short question session had a fitting end, with Lib Dem Lord Roberts of Llandudno, highlighting a recent performance of the Citizens of the World choir, an example of people getting together to improve our community and lives.

And in a world of ageing populations, falling birthrates, with so many pressing issues facing our societies that require human effort to solve, we cannot continue to make movement so difficult, dangerous and damaging, to see so many lives lost, and bodies and minds scarred by the experience. Safe, orderly routes to safety – for the millions of climate refugees we’re already seeing and so many others victims of the destructive politics foisted on the world by colonialism and post-colonialism – have to be a priority, and part of the political route to establishing those has to lie in telling the stories of past migration.

PS. We hope you enjoyed this article. Bright Green has got big plans for the future to publish many more articles like this. You can help make that happen. Please donate to Bright Green now.

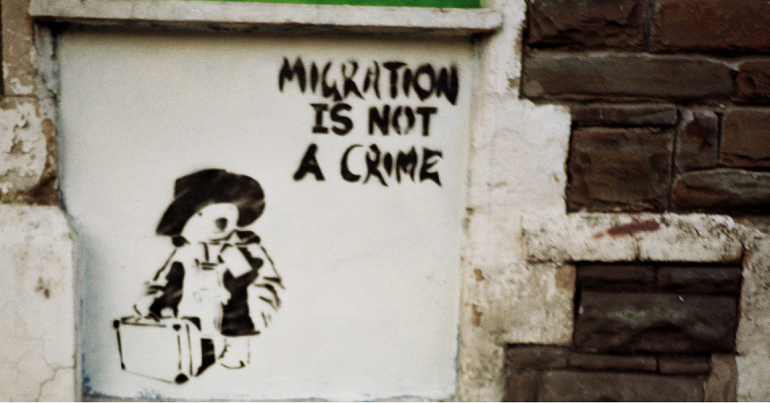

Image credit: Walt Jabsco – Creative Commons

How odd: I posted a comment yesterday, politely disagreeing with this article and pointing out that its arguments have been refusted by Douglas Murray’s 2017 book ‘The Strange Death of Europe’. It vanished, though I had filled in all the details correctly. I wouldnn’t like to believe that the author of this article doesn’t believe in free speech and stimulating discussion.

I have to point out, as politely as possible, that all these arguments have been refuted by Douglas Murray in his 2017 book ‘The Strange Death of Europe’.