Who exactly were the “Green surge”?

The figures are frequently thrown around Green circles – 14,000 members at the start of 2014, 67,000 by the General Election this year. The ‘Green surge’ is fairly well documented, at least on the interwebs. But who exactly made up the ‘Green surge’? Everyone has a theory – generally focusing on young educated lefties – yet there’s been very little fact-finding.

A completely ignored paper published last month – ‘The Other Insurgency? Greens and the Election’ – sheds a lot of light on the Green surge throughout the UK. I wrote about how the Green surge happened according to the author, James Dennison, a few weeks ago. Dennison’s study said that the Greens’ backing of ‘consistently popular policies’ – renationalisation of the railways, a higher minimum wage, a fully-public NHS and so on – was a large driver behind the surge. On top of that, the Greens became the anti-UKIP party – ‘carv[ing] themselves a niche’ as the only truly pro-immigration party.

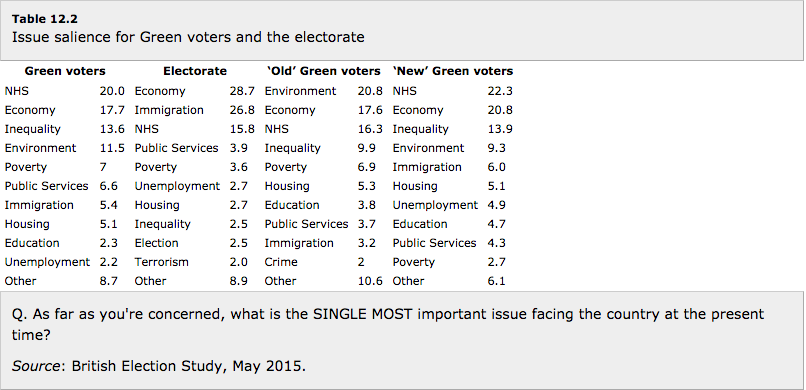

But who did this attract? ‘A majority of Green voters were under the age of 36, and nearly 17% were students, over double the proportion of any other party’. Greens were the most likely to have degree, and the most likely to be in professional/managerial positions – not far off the Lib Dems. They were most likely to have specialised in the humanities at uni. And over two-thirds say they are non-religious – 69% compared to 46% for Labour and 45% of the wider electorate.

Here’s where it gets interesting though. Despite the Greens’ left-wing policies…

“On specific economic policy issues, those voting Green in 2015 tended to be very slightly less left wing than Labour voters: 71% of Greens believed that the government should redistribute incomes, a very slightly lower figure than the 74% of Labour voters”

It’s still ‘significantly higher than the 53% of British electors who supported such redistribution’ – but it’s insightful nonetheless. Labour still had its old-Labourites, even under a not-particularly left-wing leader.

The study makes clear that ‘Green voters are highly similar to Labour Party voters on the traditional left-right spectrum’. But the demographics are clearly very different, as the table shows:

The demographics feed into the ideological backgrounds of Green vs Labour voters – even if the policy preferences of the two groups of voters are similar. Fundamentally, Greens come from the ‘new politics’ of the movements of 1968 – environmentalism, anti-authoritarianism, left libertarianism, and of course intense social liberalism. Greens don’t take all their politics from class. It’s bigger than that…intersectional, if you like. ‘On issues of ‘post-material’, ‘new’ or ‘integration-demarcation’, there are consistent and striking divides’ by Green and Labour voters.

Green voters are the most pro-EU, the most pro-immigration, the most environmentalist, and the most anti-authority (the first bar):

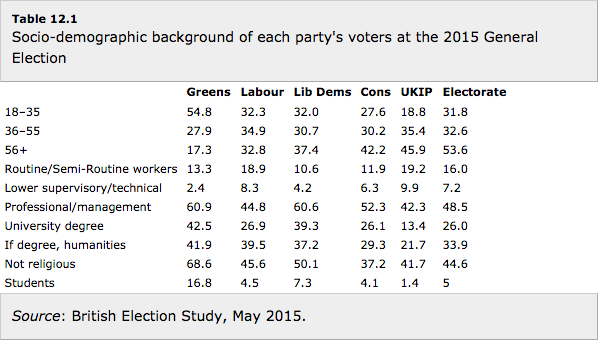

Up to now though, we’ve been looking at all Green voters – old and new. To get to the bottom of the Green surge we have to break down those two groups. And they are very different groups indeed.

The top issue for long-term Green voters is the environment. The Green surgers put the NHS top. Both put the economy second, although this says little in terms of economic policy specifics. But immigration doesn’t even come in ‘Old Greens’ top five priorities – it’s 9th in fact, compared to 5th for ‘New’ Greens. The environment, perhaps tellingly, is placed 4th by the Surgers – fewer than one in ten see it as the most important issue.

There’s a killer line though – ‘as the Greens improved in the polls, the most strident environmentalists made up a decreasing share of Green voters’. Popularity is inversely proportional to ‘greenness’, it seems.

Greens overall though, are basically Lib Dems, in terms of demographics. The ‘average’ voter for both is uni-educated and in a professional job. Greens in 2015 were where the Lib Dems were in 2010 – the liberal-left protest vote. And it is, in a way, a protest vote. 7 in 10 Greens don’t trust MPs. Three quarters are dissatisfied with British democracy (understandably). It puts them almost identical with UKIP on both these issues.

Protest voters are clever too, though. The Green vote goes up when seat marginality goes down – a 1 percentage point difference (significant when you’re playing with 3 or 4% of the national vote) in a 10k majority seat compared to a marginal one.

And so, we come to Corbyn. The study concludes:

“As partisan dealignment continues to fragment the party system, those voters who remain engaged have become more critical and their voting behaviour less predictable. For more voters than ever before, in 2015 Natalie Bennett’s party was attractive because it provided the best product in an increasingly crowded market.”

What is the best product on the market? Voters aren’t tied to parties these days. They are shoppers. They are party hoppers. They are not loyal. They do not stick around and hope for the best. They jump ship – frequently.

So where does this leave the Greens when Labour present themselves as a left-wing party under Corbyn? Most of Labour’s new backers are the same type of young lefty that backed the Greens in May. Their policy preferences are almost certainly the same (I know – many of my once-Green friends are now joining Labour).

We have to find our position in the spectrum now and solidify it. The Green Surgers’ policy priorities are very similar to Corbyn’s (if not Labour’s as a whole). To keep them on board, the party has to show that the Greens are the best party to actually stick with these policies. Reverting to pure environmentalism – without a focus on social justice – will just leave us as a rump ‘Old Green’ party, while the ‘Green surge’ becomes a ‘Green purge’…

Your conclusions don’t follow. The text shows Green & Labour voters are different, anti authority and authoritarian socialism don’t fit.

What i think the article is pointing to is the position of ‘Green surgers’ in relation to Corbynism. The poll results relate to Labour under Milliband. How can we prevent a leeching off of new Green members to Corbyn’s labour. How long will Corbyn lead Labour for and if he survives how many of his Policies ( Not Millibands) will survive without being diluted or abandoned. Only the Anti-Austerity line has so far been approved at Labour Conference and that is easy for a Party not in Power. Corbyn recently announced that while he opposes Tory cuts, he supports Labour Councils ‘having’ to make those cuts. Our Labour Council in Brighton is happy to use this quote to defend their savage cuts in local services and council tax rise on the lowest income residents. In fact it’s the only thing Warren ‘Kendalite’ Morgan has agreed with JC on so far!