Stoke-on-Trent and the working classes aren’t broken; our political system is.

Many will have breathed a sigh of relief this week when news broke that UKIP resoundingly failed to win a parliamentary seat in Stoke-on-Trent, often touted as the Brexit Capital of England. Yet, that relief cannot paper over the cracks that now gravely threaten the foundations of our democratic political system

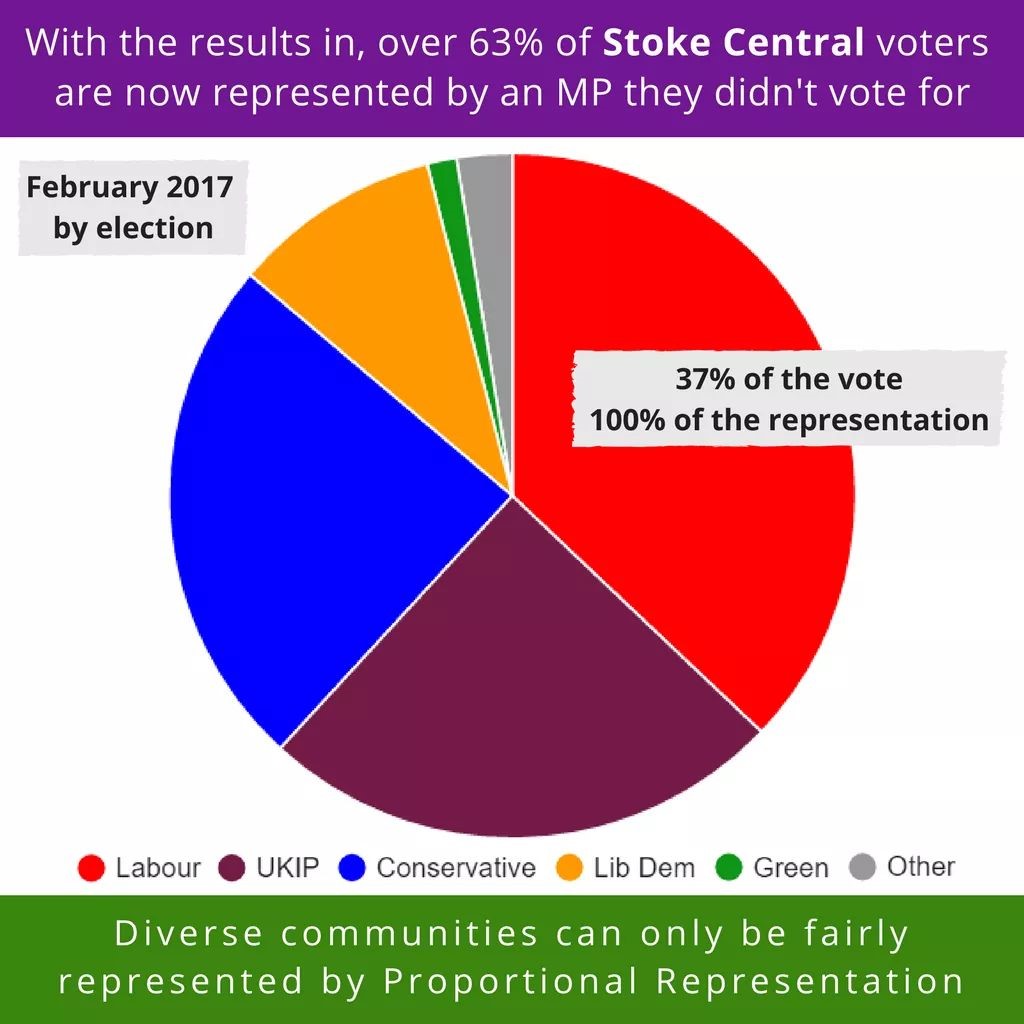

In the 2015 General Election, Stoke Central had the lowest turnout in the country, with just 49% of those registered to vote going out on polling day. In Thursday’s by-election, despite weeks of intense media coverage, and the election tipped as a turning point for the city and for the national political landscape, that figure plummeted further, with a turnout of just 38%. Labour held the seat with just 37% of this.

Across the political spectrum, campaigners on the ground talking to constituents reported widespread mistrust of politicians and disenchantment with politics in general, with many openly declaring that they had no intention of voting and that it mattered not who represented Stoke, they would do so in name only.

Helping Gareth Snell win the stoke by election pic.twitter.com/WZIG449Pxc

— Peter robinson (@peterro43898916) February 21, 2017

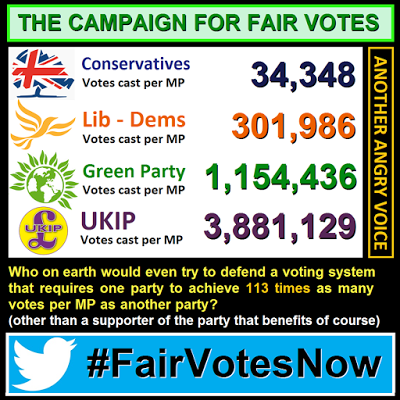

Anger and disillusionment is not exclusive to Stoke-on-Trent; across the country, turnout in elections has been pitiful and registration of voters has declined, a problem that is particularly evident amongst younger people. With so many people feeling disconnected from the political process, can we reasonably be surprised that so few engage with it? The last General Election was the most disproportionate in British history, giving us a government dominated by a party who secured just 24% of possible votes (1,334,920; total electorate: 44,722,000), and yet returned 331 of their members to parliament, out of a possible 650 seats.

Labour have spun the result in Stoke Central as a victory, triumphantly seeing off the threat from UKIP and proudly holding onto a seat which was once deemed Labour’s safest in the country, held by them since its creation in 1950. Yet, with almost two-thirds of registered voters staying at home, and almost two-thirds of those who did vote backing one of the other nine candidates, this result isn’t truly a victory by any standards. Gareth Snell secured 7,854 votes in a constituency with 55,572 registered voters – meaning that just 14% of registered voters in the constituency backed the person who now represents them as a Member of Parliament.

Far from an isolated incident, this picture is replicated up and down the country. Under the First Past the Post electoral system (FPTP), millions of voters are excluded from representation in Parliament as regulations limit MPs to only supporting people living in their designated constituency. So-called “tactical voting” is rife, as people battle the constraints of an archaic electoral system to try and establish some semblance of representative government. Ultimately, the only outcome is that the bubble of Westminster becomes more and more removed from the realities of people’s daily lives, and the disconnection between the two drives resentment and mistrust. Why would anyone take the time and energy to invest in such a governance structure?

The Green Party has long supported campaigns for democratic reform, including moving away from the First Past the Post voting system towards a more proportional system. In 2007, the Single Transferable Vote (STV) system was introduced for local elections in Scotland, and the results saw 74% of voters getting their first choice candidate elected, as opposed to just 52% under the previous FPTP system. Proportional Representation systems also increase the range of parties elected, meaning that smaller parties are far better represented, and that elected bodies are more reflective and responsive to the electorate’s spectrum of political views. Imagine how different Westminster would operate if the 29 million people who didn’t vote for the Conservatives in 2015 were properly represented!

Where Stoke-on-Trent once flourished as a pioneer of industry, the decline of pottery, steel, and coal has left the city on its knees, with prospects of a once stable industry job replaced by the insecurity of the “gig economy”, and thousands of people struggling to make ends meet on zero hours contracts and unfeasibly low wages. The Conservative government’s austerity policies have hit the city hard, with homelessness on the rise and poverty through the roof. If ever a city needed a strong voice to speak for its needs in Parliament and be its champion, it is Stoke. If ever there was a need for people to feel that their voices are heard, it is the people of Stoke. Despite its difficulties, Stoke-on-Trent is a fascinating city with a proud history, and the potential to become a beacon of progress, but until its people can trust in the political process and feel that they are truly represented, turnout at elections will continue to fall away.

While residents of Stoke Central wait to see if it will be “politics as usual” under their new MP, political activists across the spectrum mustn’t overlook the issues exposed by this by-election. Low voter turnout is a symptom of a decaying electoral system, and the only antidote is urgent and dramatic reform.

Leave a Reply