On QE, overproduction and the economics of a negative carry universe.

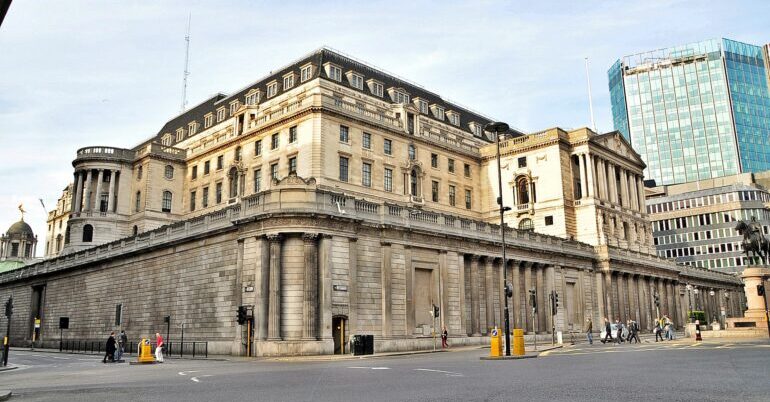

In the run up to last week’s announcement of more QE from the Bank of England there have been a couple of interesting posts on FT alphaville talking about “negative carry universes” and why banks are finding it so hard to make money recently, and why despite all the money being pumped into them we’re still not seeing any increase in lending.

For one there’s a bit of a confusion amongst a lot of people about what the point of QE really is and what base money and central bank reserves really are, but let’s leave that to the side for now (important as it is to understand).

What I found really interesting was the post suggesting that the reason we’re in a negative carry universe is not that banks made mistakes, but that we’re seeing a fundamental restructuring of the underlying economy, away from scarcity and towards abundance.

“what if the banking crisis is less about bad lending decisions and more about overly successful investment? (We appreciate this is not conventional thinking, and that many will find this idea sacrilegious, but please run with our hypothetical scenario — just for fun.)

First, consider some of the evidence. We know the Western economy has been plagued by overcapacity issues. Output gaps have been negative not only in developed countries, but on a global level.

As the Fed puts it, this means the economy has dropped below its potential.

Yet there is something different about this overcapacity problem compared to others in previous recessions. As the Fed wrote in 2009, this one seems to be driven by a supply (or happy) shock is not restricting productivity”

Why does this matter to banks? Well, banks are supposed to operate, and create a profit, by matching people who want to lend short term and borrow long term. That is savers want to maintain their liquidity (access to their money) but people and companies want to borrow on a longer scale to invest in production or property and so on (and you don’t want your bank to suddenly recall its loan on no notice or apply for a new one every week). Normally the yield curve slopes upwards over time, so interest rates for long term loans are higher than short term loans – you pay a higher rate on your mortgage than you get on a current account – and so the bank makes a profit off this difference in rates. This is positive carry.

But since the credit crisis this hasn’t always worked as it should.

“When there is a uniform liquidity crunch it results in higher interbank rates (cue Liebor madness), since banks compete with each other ever more aggressively for funding…

The hope was that this was a system-wide liquidity crisis not a system-wide insolvency crisis. Provided the central bank could tide banks over with liquidity in the short-term..

Unfortunately it soon transpired that liquidity was not enough to bridge the short-term funding gap. Banks also needed to be recapitalised in order to stay solvent.

Again, this was justified because it was hoped that upon recapitalisation and with liquidity support banks could soon reset and become profitable again, being able to support themselves.

Yet, this failed to happen.

More QE was attempted on the belief that the system still needed more liquidity.

Yet this too failed to help.”

And so we end up where we are now.

“The battle is no longer about liquidity but about preventing the negative carry universe from impairing bank profitability forever. Indeed, unless a positive carry is re-established banks will never be able to support themselves, for they will never be able to make money according to the old model.”

So how does fit in with the first story I mentioned about over-production?

Another way to look at the normal functioning of banks is to think of it as them borrowing money from the future to invest in future goods by paying for production today.

“balancing tomorrow’s shortage of goods against today’s relative under supply of money. So by extending credit at your own risk (shorting money) on the hope that it leads to the increased production of goods. We call this process investment lending.”

Basically money will grow over time and goods will be used up, unless we use future expectations of money to invest to create more goods.

And here we come to the underlying problem. Banks didn’t get into trouble because they made bad decisions (though they probably did make bad decisions) – the corollary of which is that given support and better decision making everything will work out – but because the underlying future distribution of goods and money is changing.

“As our charts attempt to explain, this could be because in a negative carry universe — one in which goods, collateral and assets are expected to permanently outnumber money in the future — bank profits can only be achieved through pariah practices rather than lending. Banks are ironically encouraged to destroy capacity, disincentivse investment, borrow money from the economy rather than lend it, and hoard wealth. All phenomenons we are currently seeing. All phenomenons which are economically destructive.”

In the end maybe we’re not just seeing a crisis of financial management but a real crisis of over-production; automation and increasing productivity are increasing supply, stagnating wages and personal debt can no longer maintain demand to keep up and opportunities for productive investment are disappearing.

“A man who has produced, does not have the choice of selling or not selling. He must sell. In the crisis there arises the very situation in which he cannot sell or can only sell below the cost-price or must even sell at a positive loss….

As Mill says purchase is sale etc., therefore demand is supply and supply demand. But they also fall apart and can become independent of each other. At a given moment, the supply of all commodities can be greater than the demand for all commodities, since the demand for the general commodity, money, exchange-value, is greater than the demand for all particular commodities, in other words the motive to turn the commodity into money, to realise its exchange-value, prevails over the motive to transform the commodity again into use-value…

Crisis is nothing but the forcible assertion of the unity of phases of the production process which have become independent of each other.” Marx – Theories of Surplus Value, Ch 17

Peter, the point of the base money confusion article was that lending isn’t directly related to central bank reserves – those control inter-bank liquidity – so I don’t think you can claim she’s confused on that point then say the say thing essentially.

Her broader point was an attempt to explain why lending isn’t happening and rates are so low, so I think it does add to the reality.

And though credit creation is by no means as simple as it used to be (borrow short lend long), that’s still the underlying principle and how they’re “meant” to function. As Duncan Weldon (http://touchstoneblog.org.uk/2012/07/the-macroeconomics-of-a-negative-carry-universe/) said in relation to the alphaville series:

“Of course financial innovation has transformed banking. Banks no longer need deposits to fund lending – instead they can themselves borrow from wholesale markets. But the principles of positive carry and borrowing short to lend long remain the same.”

And for the record I think Andrew was pretty much right in that previous debate about money.

Dan – you are correct in saying “Instead of central banks leading monetary policy, money supply is exogenous – private banks create credit, and then the central bank must act to follow this up with reserves,” but do you mean “endogenous”?

Alasdair – Kaminska makes some interesting points, but also seems rather confused. Dan has quoted where she understands some key principles about money (something which Bright Green contributors got horribly confused and quite abusive about in this ill-tempered and quite odd debate): http://brightgreenscotland.org/index.php/2011/02/banking-and-money-creation-part-1

But Andrew Lainton points out where she gets muddled:

“This goes to an underlying issue in your writing – you ‘get’ endogenous money, but carry around a huge baggage of ideas and terminologies re money which only made sense with exogenous money – money multiplier, inside outside money, high powered money, base money etc.

Yes money depreciates, always has and always will like any commodity, and you make a profit on any commodity if the economic rent from commodity ownership over the period of production is greater than depreciation/amortization associated with that commodity. The source of depreciation here is the gap between Inflation and the rate of profit of the use to which money is put.”

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2012/07/04/1071311/the-negative-carry-universe/

Similarly, I see your ideas of banks lending out savers’ deposits, or “borrowing from the future”, to have little connection with what banks actually do, ie lend as much as they feel they can according to the presumed creditworthiness of borrowers, with no regard at all to reserves, central bank expectations etc.

If lending is falling, if loans are harder to come by, it is because of presumed creditworthiness and demand, not at at all because of central banks or interest rates.

Interest rates are negative at present. Funds are buying German bonds at negative cash rates, never mind real rates.

That’s fascinating. But I’m not sure what the idea of a “negative carry universe”, whatever that means, adds to that stark reality.

Except that the alphaville article isn’t saying that central banks no longer have any power to lead markets, just that people misunderstand what reserves at central banks actually are. And their description of what happens isn’t that different from textbook ones. And money supply isn’t actually that important, people like positive money get all hung up on the idea of credit creation, as if the fact that that’s what banks do is some awful revelation. It’s really not, and changing that wouldn’t alter any of the real problems in the economy, in fact in the absence of any broader changes it would probably make things worse by massively reducing the amount of capital available for productive investment at any one time.

Great observations about money creation from the quoted article – http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2012/07/03/1067591/the-base-money-confusion/

“Every time a bank lends, it actually creates brand new credit. This is done by creating a liability for the borrower on one side, and an asset for itself, which can then be sold on, on the other side.

There is no limit to how much banks can expand credit in this way. The same base money is passed around like a hot potato, creating offsetting assets and liabilities every time it hops. Another way to look at it is that base money is what’s left over after all banking liabilities (deposits) and assets (loans) are offset against each other.

In systems that carry minimum reserve requirements, base money must at the very minimum cover these required ratios. In these cases, when credit rises base money must also rise or else banks could fail to meet such ratios. However, the central bank almost always provides enough base money to ensure that these ratios are met.

In systems that don’t carry minimum reserve requirements, base money becomes a function of banks’ own liquidity needs, and adjusts in line with risk and non-performance of loans.”

Essentially we are now in a situation the complete opposite of what traditional textbooks have taught us. Instead of central banks leading monetary policy, money supply is exogenous – private banks create credit, and then the central bank must act to follow this up with reserves, otherwise the system will collapse. Check out positivemoney.org.uk for more about this problem.