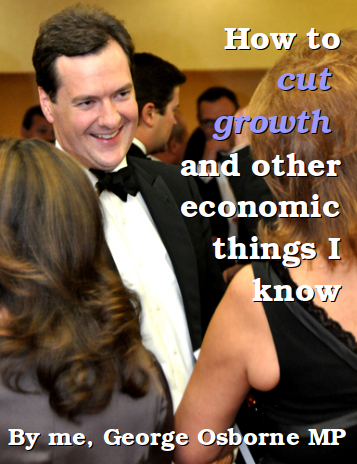

Eight steps to cut economic growth, by George Osborne MP

1. Encourage savings and inheritance

Encouraging people to pass on their wealth unused to the next generation is a great way to reduce the amount of money flowing through the economy. I’ve not yet been able to deliver my full plan for cutting growth in this way, but you can be sure we will deliver this plan once the opportunity arises.

Tories to hike inheritance tax threshold to £1m

Our new policy for social care is centred on home-owners. Naturally reducing care costs for people is helpful in general, but we’ve made sure our plan delivers as little benefit to the wider economy as possible. By focusing on delivering benefits to people who already have assets, we’re making sure they keep them and pass them on to the next generation, rather than have that money put back into the economy.

2. Cut welfare

Trimming down welfare payments takes cash away from people who don’t have excess income. As these people are very likely to spend the money they receive, giving money to them is a good way to get money flowing round the economy. By cutting welfare, we’re keeping this to a minimum. Chop chop chop!

George Osborne in £10bn benefit cut vow

3. Print money, but give it to people who won’t spend it

Although we’re not for more borrowing, we are happy to print a small (£375bn) amount of money for the benefit of our pals at the banks. This is a highly effective way to slow economic growth, as compared to other forms of spending (see above and below) it doesn’t go very far, and may very well end up being spent on the kind of financial products that caused the financial crisis.

4. Cut departmental budgets

Taking money out of Government services directly raises unemployment, taking money out of people’s pockets and taking custom away from procurement services and contractors. That’s why cutting departmental budgets is such a great way to take money out of the economy and cut growth. Onward!

Osborne to unveil extra £2.5bn in cuts

5. Split the country into bits

Our compelling agenda for a somehow better Britain is doing wonders for the ‘Yes Scotland’ campaign, helping Scots see just how much better a job they could do running the economy themselves. Once their gone we can kiss that oil revenue goodbye!

Eastleigh proves gulf exists between Scotland and England

6. Confuse small businesses with new tax procedures

I’ve just cut National Insurance for small businesses. Since new and small businesses are a key way in which an economy stays dynamic, this should be good news, but it’s not so simple. I’ve cut corporation tax for big business but not for small businesses: small businesses must now pay a different rate. So plenty of new systems to plan for and make sense of, but not much money to be saved.

Osborne announces “major simplification” of business tax

7. Invest in unproven expensive energy sources and create uncertainty over reliable ones

Nuclear power and gas fracking are risky and expensive, so I’ve promoted them above simpler renewable technologies which could deliver in short timescales, to make sure we pay higher costs now, and don’t get any benefits until many years in the future.

Tax allowances for investment in shale gas

Wind farms: Row after minister says UK has ‘enough’

New nuclear power plant at Hinkley Point C is approved

8. Apply tax breaks, but only to people who already have excess cash

The new 45p top rate of tax and higher ‘personal allowance’ of £10,000 are proud achievements, cutting the tax of people who are in work and already making a money. This is a big part of my economy-crashing strategy, as it means that only people who already have money get assistance. As they don’t need much extra cash, most of these lost tax receipts will go into bank accounts and sit quietly for many years to come.

George Osborne cuts 50p top tax rate

As you can see, by following my trusted formula, you get dependable results every time. Low growth, no growth, even negative growth is possible! The likes of Germany, USA, Iceland, and other recovering economies have a lot to learn about macroeconomics from me, George Osborne MP. It’s amazing to think that when I came into this job I only had a BA in Modern History.

This site really has all the info I needed concerning

this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

OK, let’s look at it another way. The discussions about “printing money” quickly go off track, as it seems people want to label each other as “Positive Money loonbuckets” or “Weimar hyperinflationist scaremongers”. I suppose some people do use the term “printing money” as shorthand for “debasing the sovereign currency, the slippery slope to penury and damnation”, but I don’t. I see it more as a matter of fact. Perhaps I should use another term.

Let’s recognise that when the BoE does QE, it creates a resource for itself which has not previously existed. It doesn’t sell gold or anything else to acquire the assets it buys with QE, it just allocates itself the extra capacity to do so. In the language of the Kaminska article you link, the BoE has not given up redemption rights, or used up some “tomorrow money”; it has created the additional capacity to buy the assets which it purchases, without sacrificing anything to do so. I think everyone recognises that.

Is that printing money? Well, you could say that it’s not money unless it enters the economy, ie adds to the total resources which people have available to purchase goods and services.

If QE simply results in a change in the composition of the types of asset held by banks, then that isn’t new money in circulation and could be said not to be money at all (at least in the sense we commonly understand money), so the act of creating the assets which the BoE used to buy the bonds from the banks wasn’t “printing money”.

However, the express aim of QE was to get banks lending more money (creating more money) to real people for them to spend in the real economy. One rationale for this was that banks’ reserves were too low so they couldn’t lend, but that’s a red herring. Banks make lending decisions based on whether there are creditworthy borrowers, not based on their reserves. (See the first link under the Kaminska article, “Money Multiplier Fallacy”, for more on this). Another explanation was that the BoE buying up bonds would lower the yield, pushing people towards forms of investment which would give better returns, like other forms of lending.

Either way, the aim of QE was that it would result in more money circulating in the economy than before QE. Whether the transmission mechanism for this would have been increasing bank reserves, or displacing investment into other lending, or increasing confidence in order to stimulate demand for loans, is probably irrelevant. It was intended to result in banks making more loans, ie creating new credit for circulation in the real economy. Arms-length money-printing, if you prefer.

It was largely unsuccessful in this, because the problem is a lack of creditworthy potential borrowers.

In policy terms, the more important point is your second para. I agree that the government should be able to spend on productive activity without using QE. However, the Maastricht Treaty expressly forbids monetising government debt.

It would be simpler to recognise that as governments can and do create money as they please (but have largely outsourced this function to private banks, disastrously), then they should just accept their responsibility to do so, especially in times of recession.

But that seems to be incompatible with EU membership, as well as with mainstream economic wisdom.

It’s not printing money – see, for example, this to explain the difference http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2012/10/02/1187841/dont-call-it-money-printing-rubiks-cube-edition/

If the government wants to spend on productive activity, it can do so, it doesn’t need to use QE to do that and that isn’t the role of the BoE.

Gosh I don’t remember writing this! It’s wonderful having staff isn’t it?

Onward!

Alasdair – yes it is printing money (“printing money” as in creating money from nothing, ie electronic credits, rather than physically printing banknotes).

The BoE increased its own balance sheet by simply wishing it so. It is the self-same magic money tree which Cameron and Osborne assure us doesn’t exist.

The rationale for doing this and giving it to the banks was that they would lend it on, but because they are in many cases insolvent, they used it instead to prop up their own fraudulently mis-stated balance sheets. Many companies don’t want loans anyway, they already have money, the problem they face is lack of demand.

As Gary says, creating money in this way but spending it on creating productive activity would have made far more sense; but that would contradict the prevailing orthodoxy.

Well it made me laugh anyway, in a rather bitter way. I don’t really understand economics, but I’ve heard you lot (and a few top economists on the wireless) say that Osborne’s policy won’t clear the deficit and will make things worse rather than better. You seem to have been proved right so far. As a green the only thing that’s good about it is that growth has slowed down. That’s meant to be a good thing isn’t it? For the environment at least.

Ali – I think Ric is saying it slows growth compared to the alternatives, that is to say, creating the money in much the same way but spending it on productive work rather than on the buy-back of government bonds or similar.

Nothing wrong with a BA in Modern History!

It’s maybe a semantic point, but QE really isn’t printing money, nor was it really ‘given’ to anyone. The BoE increased it’s own balance sheet and used those reserves to buy assets from banks. Banks only indirectly benefit from the increased liquidity and upward pressure on asset prices due to the increased demand. The government benefit too, as the £35bn they used to reduce the deficit shows. In effect that was the government creating money for spending on services and investment. We can critique how QE has been handled and how effective it has been, but I don’t think it’s fair to say offhand it slows growth. Or that the headline number of £375bn is that meaningful. There may be better monetary policies, but Osborne’s job is fiscal policy, and that’s what he got wrong.