After 160 years Central Scotland has had enough

When new technology offers us great promise – and the new gas boom certainly does, offering up cheap, clean energy and jobs galore – it’s worth taking time to consider what lessons can we learn from history.

Discussing the announcement of a gas industry-financed report proclaiming ‘drill baby drill’ for the UK, Newsnight reporter Andrew Black says Scotland’s shale oil was “a once proud industry that years ago was the envy of the world”. We are often proud of getting through traumatic events. Few industries have given a place as much trauma as the fossil-fuel extraction industry. What is remarkable is that the quite small patch of central Scotland where new gas drilling is being proposed is the very place that has perhaps the longest history of this trauma.

From shale oil to coal to the North Sea, the central belt of Scotland has seen it all before. Boom and bust, pollution and catastrophe, and then the inevitable mess for communities to clean-up. Proposals by Dart Energy to drill for coal-bed methane on the River Forth could be just another chapter in this story, but encouragingly, local people might be poised to make history.

Bings and the first booms

It’s been almost a century since Scotland’s shale ‘bings’ (shale spoil heaps) have been out of use, and much seems to have been forgotten of the true nature of the industry that created them.

Central Scotland’s history of oil and gas began with shale oil, which for a brief period made Scotland one of the world’s largest oil exporters. Beginning in the 1850s, it was a boom industry in the time between the abundance of whale oil and Texan black gold. Entrepreneur James ‘Paraffin’ Young invented a process to produce easily transportable and relatively safe lamp fuel which made him very rich, and in terms of sheer scale left the most astonishing footprint on the Scottish lowlands.

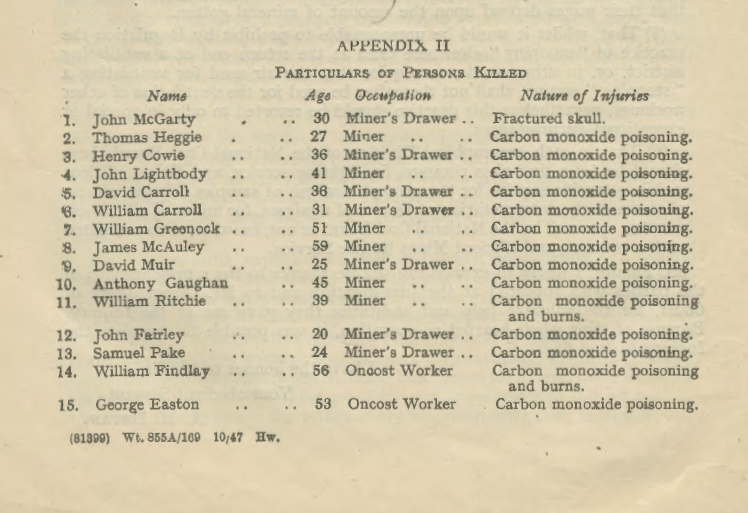

This land is, of course, totally lost to agriculture, but the human cost of the boom was greater. Places such as Burngrange, W. Lothian suffered greatly in incidents like that in January 1947 where rapidly spreading fires took the lives of 15 shale miners. Epidemiological studies from this time reveal considerable damage to health including skin and respiratory conditions (Ref.1). Unlike the James Youngs of this world, shale miners did not die old.

Yet shale oil’s impact on the central belt was dwarfed by later developments. The deepest scars in the area were left by the coal industry. At its height it employed over 140,000 people in Scotland. Mining families made up 10% of the population.

In the 10 years from 1877 to 1887 Scotland lost 343 people in three disasters with workers killed in mines kept in appalling conditions. The outrage and courage of those they left behind was a major driver to the budding Labour movement. Like shale mining, numerous effects shortened life-spans. Although great strides were made by the unions these mines were never safe, with subsequent disasters taking lives right up to the 1960s.

Central Scotland’s deep mines have now gone, but their impact still remains. They left their slag heaps and their bings, and occasionally the mines remind of their presence when a house sinks into an old coal seam, as happened in Edinburgh in 2001.

Remaining open-cast mines have now gone under, and the liquidation of Scottish Coal is providing nowhere near enough assets to pay for the sites’ restoration. What a mess.

Communities built for the pits defined themselves by coal and shale. Now all that is left is legacy of poor health and environmental destruction.

Central Scotland and the North Sea

In October 1970 Scotland’s energy industry was transformed anew with the discovery of the giant Forties oilfield in the North Sea. A new boom was on the horizon. Many urban centres on the east coast competed for a piece of the pie. To a considerable extent, the winner was Aberdeen, but facilities were built in many places elsewhere and the largest installation of all came to the central belt: the Grangemouth refinery.

Just like the coal and shale industries before it, the oil boom brought jobs and cash to central Scotland and Grangemouth rapidly grew with its refinery owned by BP.

Carbon Trade Watch’s film ‘The Carbon connection’ revealed local people’s experiences of the refinery: people who can’t sleep at night, strange sickly smells on a daily basis, breathing troubles, and a constant threat of accidents justified a poor safety record. Most recently SEPA fined Grangemouth refinery £100,000 in 2011 after a pipeline leak and fire. The last deaths were in 1987 when three were killed by a fire which took hold of leaking gas.

Accidents seem to come in spates, and the following year Scotland was the scene of what remains the world’s worst off-shore disaster. 167 died when the giant Piper Alpha platform catastrophically exploded. 49 of the dead were from the towns of the central belt (Ref.2). Many of their homes were ex-coal mining towns.

Survivor Jim McDonald from Stirling was the last of his crew to give evidence on the disaster. He told the Cullen inquiry he only knew how to escape the doomed living quarters because he worked on rig’s construction.

Studies have revealed the deep pain of Piper Alpha’s legacy: survivors living with post traumatic stress syndrome, families ripped apart, whole communities broken.

Today North Sea oil is in decline. Tax breaks are awarded by the UK Government to encourage drilling of the last untapped acres of the North Sea, but it will do little good. Peak oil was struck in our part of the world in 1999. Lord Browne oversaw BP’s sale of Grangemouth and the refinery is now struggling to make a profit. Before long the global oil companies will pack up operations to more lucrative prospects. More towns and villages, and in Aberdeen’s case possibly cities, must lose their heart. The trauma continues.

New gas boom in the Lowlands?

In 2012, Australian gas company ‘Dart Energy’ applied for a licence to start a whole new form of mining in central Scotland. Having drilled 20 test wells already, they propose drilling a 14 commercial wells to tap methane trapped in old coal seams, known as coal-bed methane.

Coal-bed methane poses an number of environmental and health risks including well-founded records of hazardous air, groundwater and surface water pollution (Dart have ruled out the need to use the controversial ‘fracking’ process, but they do use this process at other sites). The industry have admitted that well leakages may be inevitable.

The UK and Scottish Governments say new gas is safe when it is properly regulated, yet elsewhere where regulation has been tightened drilling has stopped. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that new gas may simply be “unregulatable”, as UN Advisor Mariann Lloyd-Smith claims.

The life-span of a coal-bed methane well is 5 to 15 years, with output typically declining by “between 50% and 75% in the first year of production”. Most recoverable gas is usually extracted after just a few years. Given this sheer drop-off in production it is difficult to make a site viable without drilling wells in phases. These 34 wells at Airth won’t be enough: Dart will need to, and may have plans already, to drill further towards Stirling. There could be much more to come.

And the safety fears still abound. Just last year an explosion at a new on-shore gas rig killed 1 and injured 3 in Colorado.

The drilling site at Airth is just 5 miles outside of Grangemouth and Dart energy has a habit of reminding planners of its proximity, as if comparison to the refinery should be reassuring.

New gas comes at the right time and place for an industry desperate to find the next big boom, and they have a well funded PR machine making sure we know all about the benefits.

So what about these benefits? As we have seen, coal-bed methane can hardly be described as clean, and its global warming damage is considerable. Low gas prices have abounded on the US market, but crucially these low prices have not reached consumers. Dart’s own website says they have created at most just 37 new jobs.

Just as before, what few benefits there are accrue to a very small number of people. And more so than before these benefits will fall away quickly; a get rich quick scheme where once again all the costs are born by local people. In a very short space of time they will drill, spill, take, and leave. The rest of us are left with empty communities and polluted landscapes.

What well informed community could possibly let this happen to itself?

The beginning of a movement

Something may be happening that did not happen when the shale pits were sunk, coal was first mined, and oil was struck: people may be about to stop it.

For whilst the wisdom of their time defined that oil and coal were good for Scotland, there is not much wisdom rooting for new on-shore gas. There are people saying it, certainly, but these are industry people, the few who stand to gain.

This is partly because of the litany of environmental costs identified, the unknown risks, and to some extent the health impacts too. But what tips the balance is the overriding feeling that the benefits of this endeavour are simply not enough to make it worth it. It is too great a sacrifice and a risk to set up this industry only to see it wither in 10 years.

In Scotland, genuine alternatives are making great strides and there is real concern that a new dash for fossil-fuels could sap the energy out of the renewables industry which, evidence suggests, is well placed to sustainably power the country. Perhaps we’ve had enough of the boom and bust?

Communities at Airth and Grangemouth are responding. Hard working local campaigners have been out on the streets explaining, informing and encouraging people to take action, and it’s working: over 2000 residents have signed an objection to the proposals at Airth. Partly as a result, Falkirk and Stirling Council extended the outcome of the planning proposal, now referred to the Scottish Government, and in May the news came that Dart had halted its exploratory drilling programme.

A loose coalition is forming between environmentalists, including in the Falkirk and Stirling Friends of the Earth groups, and local residents associations. The campaign in central Scotland is starting to look like the incredibly successful ‘Lock the Gate’ campaign in Australia: an alliance of community activists, environmentalists, and conservative conservationists that has defied stereotyping. What is all the more remarkable about what’s happening near Grangemouth is that these aren’t conservative people who are simply unfamiliar with this heavy industry: they’re just sick of it.

The Scottish Government is starting to respond too. Whilst a year ago the overriding message was “it’s not our fault: talk to Westminster”, change has come in the announcement of the draft National Planning Framework which proposes ‘buffer zones’ around drilling sites. According to Friends of the Earth Scotland if buffer zones were imposed similar to those in place in New South Wales (14) more than half of Dart’s wells would be inoperable.

There is so much to be gained by this campaign. Learning our lesson from history we can turn from boom and bust fossil-fuels towards sustainable industries. We can turn our back on the solutions of rich industrialists and build an economy made for people.

References

(1) ‘Morbidity and Mortality Study of Shale Oil Workers’, Environmental Health Perspectives Vol. 30, Jun., 1979, Joseph Costello / Liddell, F. D. K. (1973) ‘Morbidity of British Coal Miners 2961-62’ British Journal of Industrial Medicine, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Jan., 1973), pp. 1-14

(2) ‘Oil Platform Disaster: Disaster dead are named’, 9 July 1988, The Guardian (London).

This is the right blog for anybody who hopes to understand this

topic. You realize so much its almost tough to argue with you (not that I personally will need to…HaHa).

You definitely put a brand new spin on a subject that’s been discussed for

many years. Wonderful stuff, just great!

my weblog; condo

Thanks for your lovely comments all. Readers may find both of the following useful:

http://faug.org.uk/

http://frackfreescotland.wordpress.com/

Ric

Thank you for taking the time to write about the local people’s views on this development. This is where we have set up our homes, build our communities, send our children to school, invest our hopes & dreams. All too often the people that are affected the most are rail roaded by companies chasing the next pound sign and as you have mentioned in your article the supposed benefits of this development are uncertain and not backed up by lessons from history

Ric

Thanks for a great article. It’s so refreshing to read the truth about CBM and shale has extraction instead of industry propaganda of which there has been much in the last few months. I am also opposing Dart Energy’s application as I live very close to the area proposed by Dart for their activities. The local campaign is gathering momentum and we shall continue to oppose this application for as long as it takes.

Thank you for this very informative article. I truly hope we “local people [are indeed] poised to make history” by taking a stand against Dart Energy and their plans.

As one of those local people you refer to (from The Inches in Larbert – well within a 2km exclusion zone, if we had one) I have objected to Dart Energy’s planning application and I have indicated my support for the demands detailed in the Community Mandate, which a group of residents, including myself, helped to put together in a series of workshops held in Stenhousemuir.

You can find out more about ‘Concerned Communities of Falkirk’, a loose group of local residents, on our campaign website, Falkirk Against Unconventional Gas (FAUG), at faug.org.uk and you can show your support using our online objection letter.

Although there are no plans for ‘fracking’ in Dart Energy’s current planning application, the dewatering method used for extracting coal-bed methane gas is risky enough.

Thanks again,

Mark Williams