Remembering Mandela

Innes MacLeod is a socialist and social justice campaigner in Edinburgh. He tweets @theInnesMacLeod.

In the hours following Mandela’s death many eulogies were written. Representatives of every shade of mainstream, western political organisations ranging from the centre-right to the slightly less centre right paid their respects. Many terms were common to these pronouncements; they described Mandela as a man of grace, resilience and most of all reconciliation. These are undoubtedly features the sadly departed man embodied but it is notable that it is these features that the media and politicians have chosen to focus on.

It makes for a very different image from how he was portrayed by the right wing, British political elite only a few decades ago. A more common description for Mandela at that time would be as a terrorist, a violent troublemaker. Margaret Thatcher famously described the ANC as a ‘terrorist organisation’ and no doubt felt the same about the organisation’s most recognisable member, Mandela. It was under Thatcher that Britain continually refused to boycott trade with South Africa leading it to be tacitly one of the most notable supporters of the apartheid regime. It was also under Thatcher that the generation of Tories who have been singing Mandela’s praises cut their political teeth.

The transformation in opinion is remarkable. Only a few members of the Conservatives, such as former MP Terry Dicks would still openly describe Mandela as a terrorist. Some, including Boris Johnson, have even spoke of how the Tories ‘got it wrong’ on Mandela. Most however have decided to conveniently forget the past including our prime minister who whilst praising Mandela as a ‘Global hero’ decided it best not to mention his involvement in a fact finding mission to apartheid South Africa funded by pro-apartheid organisations.

Though these images, the violent terrorist and man of peace and reconciliation, seem starkly different they both serve the same purpose. They serve to portray a man in the manner that best serves the neo-liberal agenda.

Thatcher’s economic ideology put her firmly at odds with the idea of sanctions. This provided her with an increasingly difficult problem. How could she and her cohorts morally justify continuing free trade with South Africa as public opinion throughout the world and in her own country was increasingly turning against apartheid? If it was difficult to portray the apartheid regime in a positive light then the obvious tactic was to cast the ANC, the main opposition to apartheid, in a negative light. By focussing on the ANC’s militant actions and aided by stories of violence in the media Thatcher could create the idea that the apartheid government was a preferable option to the violent ANC.

The violent Mandela is an image that, today, holds very little weight. His actions and that of the ANC showed that those believing them capable of governing a country (as well as any other political party at least) were not ‘living in cloud cuckoo land.’ Whatever your opinion of the post-apartheid Mandela government or the effectiveness of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in providing justice for what happened during apartheid it certainly could not be seen as the violent retribution expected by those who viewed the ANC as terrorists.

The position is therefore reversed, instead of promoting his militancy now they promote his peacefulness. They have created an image of a man with Christ-like powers of forgiveness, a promoter of peace and reconciliation and the personification of charitable giving. The fact that he was once the head of the militant wing of an organisation that desired to overthrow a government does not seem to play into this vision of Nelson Mandela. He undoubtedly contributed to this image himself, before retiring he spent a great deal of time mixing with the wealthy and powerful and promoting charity. Yet in spite of his militancy softening in his later years still within his speeches he rallied against poverty and he never distanced himself from the sabotage and terrorism that he and the ANC were responsible for instead accepting it as necessary in the face of the incredible violence of apartheid.

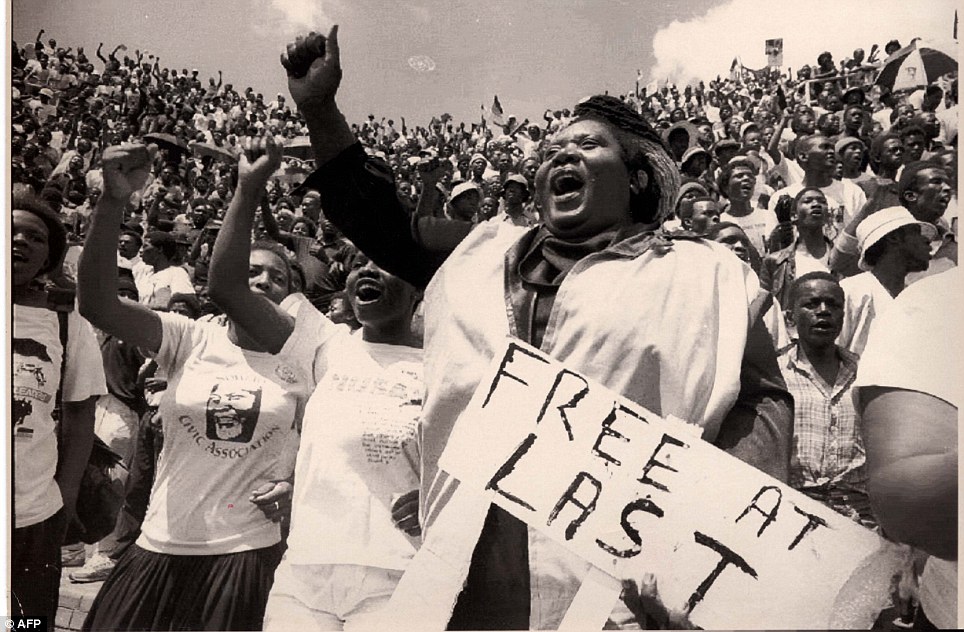

This is ignored as it would send a powerful, and in the eyes of the political elites, dangerous message. That if you want to achieve change then you must be willing to consider the use of force. If you are met with violent oppression sometimes it is not enough to turn the other cheek. It is likely that neo-liberals would prefer the history of how apartheid was defeated to be taught as Mandela bravely sat in prison waiting for everyone to realise he was right all along. So little do we now hear of the political violence and direct action that, for many who were not alive to see it, this may very well be how the struggle is seen. The image they are trying to create in the wake of his death must be understood as an attempt to promote passive protest above forceful resistance and charity as opposed to political action.

How should we then view Mandela’s legacy? Importantly we must not deify him for our cause as liberals are attempting for theirs. He was human, his achievements were remarkable and his endurance, tolerance and humanity are beyond impressive, but he was not incapable of mistakes. His time in government did not fulfil all of its revolutionary promise and to hold him as infallible would be an insult to one of the principles he fought so hard for, that of human equality. Further it would be an insult to the millions of others who fought so hard against apartheid. It was not his victory alone.

We should instead remember Mandiba firstly for what he represented. His struggle, particularly in prison, was a microcosm of the anti-racist fight in South Africa and beyond. A capable and intelligent human locked away, unable to contribute to this world due to the colour of his skin like so many others denied by structural racism past and present. His liberation showed the potential of political struggle and gave hope for the future.

Secondly we should remember his message, that we collectively have the power to make change in our society. That our desire is for peaceful resolution but we must not shy away from forceful action in the face of violent oppression. That real democracy and real equality are the bedrock of a truly fair society. That injustice of all kinds, whether based in racism, poverty or any form of oppression is something that we cannot tolerate and must oppose. To paraphrase Mandela these are ideals we should hope to live for but be willing to die for.

We will never achieve real change by abiding by the rules of the status quo. Mandela’s birth name was Rolihlahla, meaning troublemaker. Perhaps it is more troublemakers that this world needs to see the change that we would like. It is a shame to have lost such a fine example of one. RIP.

“decided it best not to mention his involvement in a fact finding mission to apartheid South Africa funded by pro-apartheid organisations” –

It was not a fact-finding trip. It was an anti-sanctions, pro-apartheid govt. propoganda trip, with an all-expenses jolly thrown in. Cameron’s defenders claim he went along for the jolly.