The fight against fossils: are we beginning to win?

Tomorrow is the world’s first ever Global Divestment Day. I’m quite excited.

The environmental movement used to be all about changing light bulbs and taking shorter showers. It is now getting organised around defeating the fossil fuel industry. How did this happen? And more importantly, how can it win?

For years environmental groups had been encouraging people to cut their own emissions. In the late 2000s we got organised to get our governments to take a lead. There was Climate Camp, “The Big Ask”, I Count, Plane Stupid, and a lot more.

We won. In 2008-9, shortly after the world economy crashed, the UK and its devolved parliaments passed world leading climate legislation.

So we asked the UN to join in. We lost.

Some people went back to the beginning and focused their efforts on local resilience, building low-carbon community projects. For a while this was the mode. It didn’t last. People weren’t just optimistic, they were angry. How could we push for the world-wide change we needed?

Sitting in the background, never quite top of the agenda, were a colourful bundle of campaigning ideas that hit climate change at the source: keeping fossil fuels in the ground.

In the early 2000s a campaign called Stop ESSO channeled the fury of environmentalists at a fossil fuel company that was worse that the worst: they funded massive climate denying PR, they were responsible for spills galore, they were even named as complicit in the Iraq war. The campaign was huge, but did not appear to have had much impact. It suffered from two fundamental problems. Firstly it asked people to boycott ESSO, but where do you then go – There is no “ethical petrol”. Secondly, even if you do have an impact on the company – what then? You can’t tell an oil company not to be an oil company. At the same time BP was trying to convince us an oil company could not be an oil company. It didn’t last.

When students started to focus on fossil fuels again in 2007 with the ‘Ditch Dirty Development‘ campaign, they didn’t make these mistakes. Their campaign wasn’t about the symptom (people putting fuel in their cars) but the cause: people getting it out of the ground. And it was cleverer than that still: it followed the money. First to UK banks, then to universities, cities and government.

Targeting the fossil-fuel brand, as Stop ESSO attempted, is not futile, but the target needs to be directed to the right outcome. We won’t get far telling people to get fuel from a different petrol garage, but we can do a lot depriving the industry of staff recruits, severing their ties with Governments, and stopping their PR machine. Fossil-fuels, not just one company, not even just one fuel, but fossil-fuels must be the target.

All other things being equal this effort could just have the effect of slowing production. Great news for the climate in the short-run, but it’d also make fossil-fuels more expensive: terrible for the poor and furthermore, higher prices will rekindle production.

The opportunity created by this movement needs to be used to redirect that capital, all the subsidies, all the patronage, all the bright people, into the emerging renewable economy. We don’t necessarily need to work out how to do that now, but we do need to understand the plan.

We need a movement against fossil-fuels that has an industry-wide aim and a long term plan. Well we’re in luck, because we do, and tomorrow it goes big.

An amazing movement is coming together to get to tackle the heart of capitalism’s biggest catastrophe:

- Fighting fossil-fuels at home: local community groups, anarchist networks and NGOs are making amazing strides to block onshore oil and gas, galvanised by real public outrage at the threat of fracking in the UK. Just last month fracking bans were tabled in Scotland and Wales, and these campaigns have brought in traditionally pro-fossil-fuel groups like trade unions.

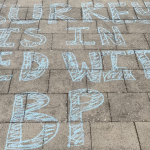

- On campuses: student groups are campaigning for “Fossil-Free” universities, not just in the UK, but around the world – first seeking to divest endowment funds from fossil fuels, then pensions and then perhaps cutting research links. This is the lead guard of global divestment day.

- Church groups are organising to divest parishes, diocese and faith organisations from fossil-fuels. Their part in the hugely successful apartheid divestment campaign was vital.

- A growing group of organisations is supporting divestment of local government, bank and pensions funds.

- Anti-poverty NGOs like the recently relaunched Global Justice Now(1) are calling for “Energy Justice” in solidarity with communities affected by fossil fuels. This builds on the work of organisations like Platform London and the London Mining Network who detail about how fossil fuel exploitation affects communities in the Global South, like Ogoniland in the Niger Delta.

- Fossil-free politics: big NGOs like Friends of the Earth and Oxfam are drawing eyes on the fossil-fuel industries’ access to the 2015 UN climate conference. This forms part of a wider need to stop the lobbying and embarrass politicians for their oil, coal and gas connections.

- Fighting fossil-fuels offshore: until it goes violently wrong there are no residents around to much care about deep-sea drilling. That’s part of why Greenpeace’s campaign against Arctic oil is such an important piece of this movement: we cannot just rely on people to stop what’s in their backyards.

- Spilling the greenwash: Art Not Oil have kept the pressure on the Tate and National Galleries in London to counter their sponsorship by BP. Fossil fuel companies get credit for sponsoring all manor of events in the UK. Art Not Oil’s lead could be taken up in many other places.

With this much going on there has been much speculation about the political and financial implications of what’s being demanded.

Much of this has coalesced around the carbon bubble – the stock market value of fossil fuels which would be rendered “unburnable” by action on climate change.

Some financial pundits have suggested this bubble poses real present risk to financial systems and as such action must be taken to invest in green alternatives.

We need to understand these arguments – and then to avoid them.

The carbon bubble does not yet exist. When Shell and BP claim that none of their carbon reserves are “unburnable” they are right. The current plan, implicitly supported by their directors and investors, is to burn it all and live in a 6oC warmed world. No: this carbon will only become unburnable if we start winning, and we have a long way to go yet.

Financiers may sell their fossil-fuel shares because they think environmental action poses a present risk to the value of fossil-fuel stocks. They may be right to do so, but they will just as quickly rebuy those shares when stock values inevitably rebound, and in the process we will have sent out a very bad message: listen to the money men.

We don’t need clever financial arguments to burst the carbon bubble. If we tackle the fossil fuel industry effectively and achieve a just transition it will deflate of its own accord.

The current financial turmoil of the fossil-fuel industry does provide us, though, with a great opportunity to question its future.

This effort is more timely still. There is widespread anger about onshore fossil-fuels and fracking. The future of the North Sea is in question. The UN is poised to meet to sign a treaty made worthless by the gentle whispers of lobbyists’ in negotiators ears. Divestment Day is coming.

Now is the time for us to draw these campaigns together to make a truly global movement against dirty energy.

It has run the world for almost 100 years. In fact it made the modern world and now stands on the brink of destroying it. The fossil fuel industry has been winning for an awful long time. Let’s make 2015 the year we started winning.

______

*Formerly the World Development Movement.

Without the coal how do you propose to keep all the refugees, that you want to have access to these islands, warm? We are far from sustaining our existing burgeoning population on non-renewables yet you want to grant access to yet more consumers.