NUS: poison or panacea to the student movement?

Watching the setting sun cast an orange glow across the English Channel from the Brighton seafront, your eyes are instantly drawn to the rusting remains of the city’s once proud pier, left out at sea as a reminder of what once was. Some would see it fitting then that NUS chose to host its arguably most controversial conference yet within eyesight of this vestige of former glory. Tabloids and Tories would have you believe that the once proud movement is now past its heyday, an irrelevance to most students due to its political posturing and inane policy proposals, and increasingly ordinary students are agreeing with them.

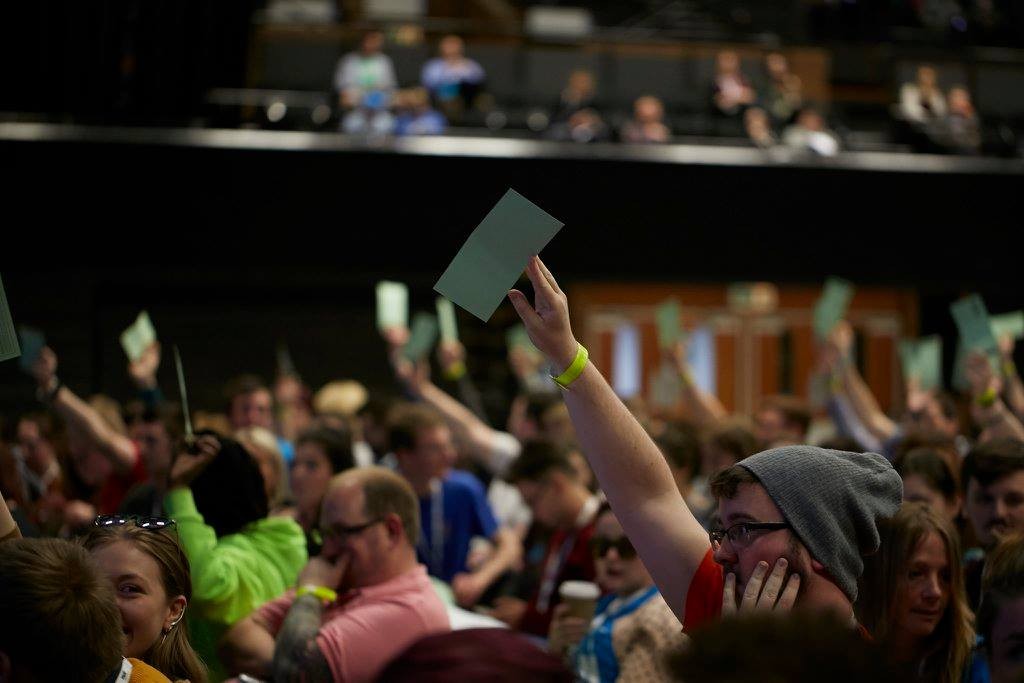

Conference is certainly a strange experience. Virtually every chair that presided over the proceedings had a vote of no confidence brought against them, usually for not picking the instigator to speak out of the dozens of raised hands in front of them (one began to lose confidence in the votes of no confidence), clear evidence of the self-entitlement that rages around the conference floor. Delegates were often told off for clapping too loudly because it might upset people. Amendments to motions were frequently longer than the motions themselves, and often felt like groups or individuals simply wanted to say exactly the same thing just in a slightly different way so as to be seen to be doing something. It was also easy to nod off at times, and even easier to think you’d awoken in the Labour Party conference with all the reverence officers espoused for Jeremy Corbyn.

But beyond the bizzarities and the misleading headlines, NUS has achieved much. This year it has spearheaded efforts to challenge the Prevent policy of the government—an agenda that is literally allowing racism and prejudice to spread across campuses and drives a wedge between community relationships. Officers have worked with students too to challenge the extortionate rents and appalling conditions that those living in student housing have to face, pushing the dodgy landlord penalty up from the initial £5000 to £30,000. It has supported student voter registration and campaigned for votes at 16, fought against the loss of maintenance grants and NHS bursaries, conducted research into the welfare of LGBT+ students, campaigned to reduce the cost of living for students and battled to keep further education adequately funded (have a search for these and more here). It is only those completely detached from ordinary student concerns themselves that could honestly say that this body of work has had little impact on students’ lives this year.

Good policy was passed at conference too. Climate change, our single biggest threat, was confirmed as a campaigning priority, with support for Student Unions’ wishing to campaign on it being approved. Conference voted to boycott the National Student Survey if the government continued to refuse to engage with NUS on its content, a move that could severely disrupt the ongoing marketisation agenda of the current government. A dedicated trans officer was passed, meaning more support for trans liberation groups and campaigns. And for all the fears around the election of Malia Bouattia and the amendment that suggested the NUS not commemorate the Holocaust (both issues substantially misrepresented by the press), numerous motions were passed that committed the NUS to rooting out all forms of racism and antisemitism both from within and from the wider student movement.

None of this means NUS is without problems.

Many things have been done this year or passed at conference that will have tangible benefits to students across the country, but much of it will not. Conference politics can be tribal and petty. Time is wasted on rhetoric and gestures that could be spent of meaningful engagement, with SUs and government. And there are deep, deep issues with how NUS engages with the ordinary student. The silver lining on all this is that these issues, whilst far from solved, were all challenged at conference.

A prominent tension at conference this year was ‘Project 100’, a centenary review of the democracy and structure of NUS, tapping into the deeper issue of power resting in the hands of ordinary students, rather than NEC hacks and SU sabbs. Nowhere was this tension more evident than in the speeches of those running to be Student Trustee. Almost all the candidates lambasted lack of transparency and accountability in how trustees currently operate within NUS, their frustration evident but also the calculation- they clearly sensed that this line would be popular with delegates too. A motion was also proposed during the AGM that would extend voting rights in officer elections to all students, not just the delegates at conference. Whilst failing to pass, it garnered some support—a sign at least that there is appetite amongst some for a more accessible and democratic NUS.

Preposterous are the suggestions, coming from both the press and the conference floor, that NUS has become too political, and that instead it needs to stop taking so many stances in order to not exclude students who might disagree with some of them. Numerous times conference was treated to a tub-thumping speech on the need to represent all student voices, and therefore make sure we didn’t do anything that was too political. One college sabb proudly spoke of the deliberately apolitical union she leads, leaving conference wondering exactly what it was that particular union did. Unions and officers should represent students yes, but they must stand up for and protect them too. Both local SU’s and the NUS as a whole have a duty of care to their members—shackling themselves to a strictly apolitical stance helps no one. The very essence of a union is a political statement: an apolitical union is a non-existent one.

The problem with NUS isn’t its battle against tuition fees and marketisation (failing to challenge these would be a serious breach of their duty of care), their support of liberation movements (that can admittedly lead to bizarre places) or their willingness to engage in direct action. Their problem is in failing to engage students that don’t sit on their committees, run a Students’ Union or rock up to Brighton in a Jeremy Corbyn t-shirt. The problem is not as giant as some think- direct action and liberation campaigns don’t come together by the efforts of a few—you need numbers for them to work. But there still remains huge swathes of students not feeling any sort of ownership over their union. Responsibility is in part on local SUs as NUS largely operates through them but not all blame can be placed here. NUS must rapidly find ways to engage the broader student movement in the good and important work it does if it wishes to not just survive but actually offer a credible threat to the machinations of the present government. Let’s hope it’s a challenge its leaders are willing to meet.

Leave a Reply