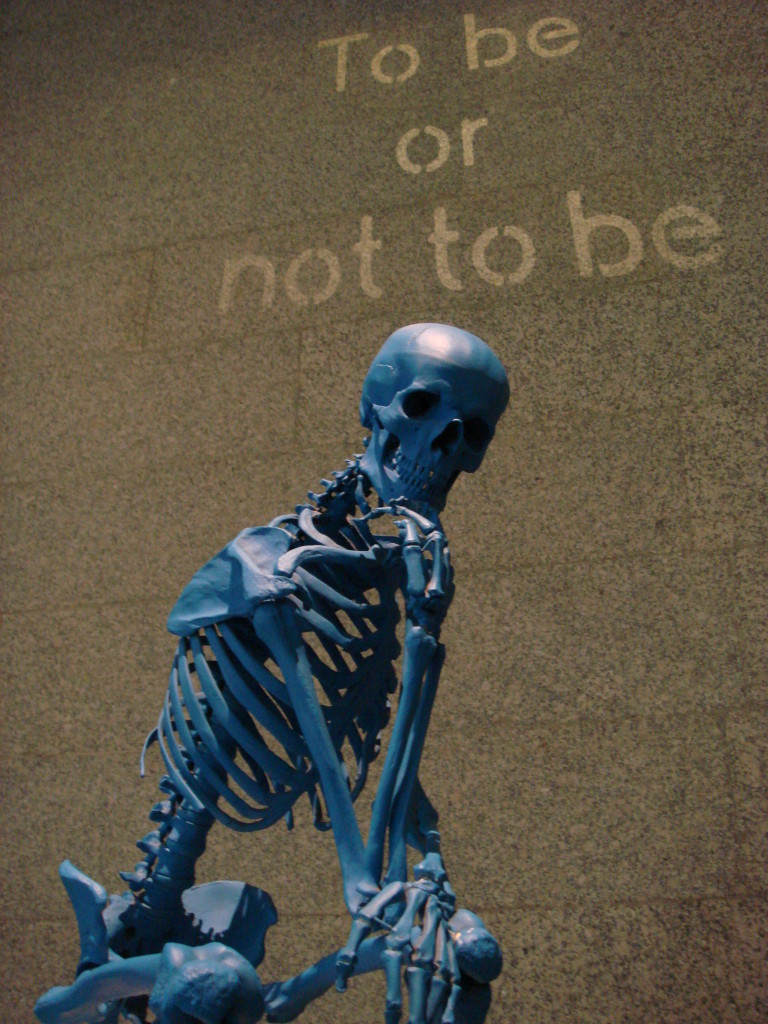

Prison reform and the arts: to re, or not to re?

I recently watched a fascinating video on Facebook.

In it we glimpse the processes of the Marin Shakespeare Company in California who work with inmates (henceforth ‘students’) in prisons to discuss and rehearse Shakespeare’s plays.

As a recent Drama graduate (and believer in the absolute benefits of Drama engagement) I loved the video. And I love the work. Shakespeare never used to be a buddy of mine but during my tenure at the University of Northampton as an undergraduate, I learnt to appreciate and even respect the deceased Bard’s work (thanks Owain! #namedrop). If you’ve ever attended a British school it’s more than likely that you’ve been forced to cross paths with the Wizard of Word-Warping and, as a result, may despise the Tongue-Toting Despot and all his unholy works. Regardless, the work of the Marin Shakespeare Company is sorely needed.

After I reposted the video a friend commented with a link to a radio documentary from This American Life, an American radio station. The documentary from 2002 follows Jack Hitt as he spends time with students at the Missouri Eastern Correctional Center. He interviews students and records sessions as they rehearse and eventually perform Hamlet with Prison Performing Arts. The documentary is an hour long so if you haven’t the time to listen to it all I’ll give you the basics: working on Hamlet with these students is a stroke of genius (also I recommend listening from 29:58 to 30:54 to gain a small understanding into the effect of this type of work).

The plot revolves around Hamlet debating whether to murder his Uncle who had murdered Hamlet’s father and married his mother. Cue antagonizing depression, betrayal, death, and ridiculous language. So what, right? Just another of Shakespeare’s brutal plays. But the genius of choosing Hamlet is this: some of the students would be able to relate to Hamlet in a way that most of us on the outside couldn’t. You may be familiar with the lengths some actors go to to achieve what they consider ‘method acting’; well, sadly, these students may have all the experience they need to understand the inner tension and turmoil Hamlet feels (as confirmed by Hitt in his radio documentary). By exploring Hamlet, the emotions some of the students may feel could be faced and through that reflection new discoveries about themselves found. The ability to express oneself in a liminal space has been shown to have benefits.

Although the prison setting is heavily codified as an oppressive structure, in those moments of discussion and rehearsal it could be said that the students were transported outside of the walls – if in imagination only – where they were no longer an ‘inmate’ with a number but a human with a name – a necessary distinction for rehabilitation. In Hitt’s radio documentary, the students describe their relationship to their characters and how it has affected them, sometimes being brutally honest about the connection they feel to their role.

The processes of these companies, and others, have positive effects on the students and their families. This inevitably calls into question the current model of prisons – an argument that has been around longer than I have. If this work has shown that rehabilitation is possible even for those considered unchangeable (see Big Hutch in the radio documentary) then why do the majority of prisons simply incarcerate more than rehabilitate? And I am only writing of one form of successful rehabilitation, there are plenty of others.

I have given examples of companies working in America but there are companies all over the world who are engaged with this type of creative output. A notable example in the UK is Geese Theatre Company. They don’t use Shakespeare as much as create interactive performances and group work with the intention of inviting the students to discuss attitudes and behaviours, amongst other subjects. These performances have had a positive influence on the students’ behaviours and can lead toward beneficial relations between the students and staff.

But what now?

We have evidence that these methodologies and creative ventures work in certain contexts. We have testimonials of life-changing engagement supported by the students’ choices not to re-offend. We have a poll from 2015 that found the general public in the UK seem to be more open to the ideal of penal reform than previously thought. We have the Howard League for Penal Reform who are a national charity dedicated to less crime, safer communities, and fewer people in prison.

And yet the powers that be dilly-dally over prison reform (yes, I know it’s complex; allow me to frustrate at you). Inconsistent leadership in government puts the public at risk, the Royal Society of Arts found whilst researching how prisons could get better at rehabilitation. We could storm Parliament with Hamlet scripts and try to bring the MPs into a discussion about whether avunculicide is ever acceptable but I doubt the response would be positive. Let’s just hope those in position of power listen to others who are trying to educate them on rehabilitation. Or maybe they really are fed up with experts. Conversely, there is a distinct possibility someone is pouring poison into the ear of the public.

I’ll finish with a corker from my main man Shakesy.

“To re [habilitate], or not to re [habilitate], that is the question”.

The work of Geese Theatre company is brilliant as well, you might be interested in the work they do as well but there is no question that the arts can help greatly in helping inmates to move on and deal with the some of the problems that led to them becoming incarcerated in the first place.