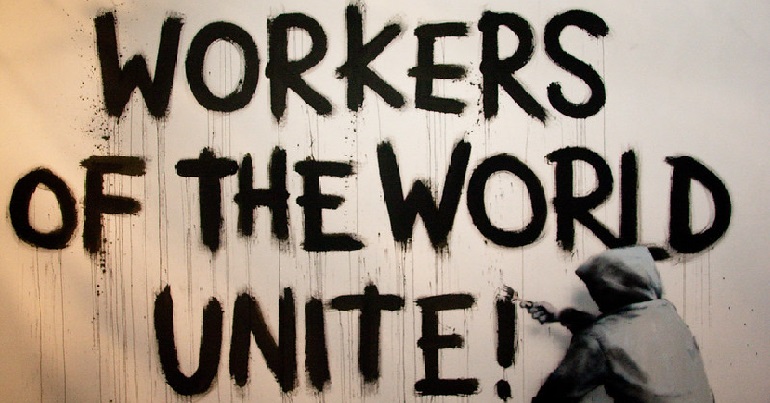

Workers need more than a living wage. They need workplace democracy.

Monday marked the beginning of Living Wage Week, a five-day working week of jamborees for scrupulous employers. But we should celebrate by testing the boundaries of the living wage model and demanding workplace democracy.

The Living Wage Foundation is an NGO with a difference. From its central London offices, it boasts a unique role among foundations: it is “the organisation at the heart of the independent movement of businesses and people” campaigning for fair pay.

By accrediting employers who commit to paying (or moving towards implementing) their independently calculated wage scheme, it has made its brightly-coloured logo a feature of corporate websites. Judging by its own homepage, the level of buy-in seems impressive: from Oxfam to Everton FC, organisations from across various sectors have made the pledge to pay a living wage.

Their intellectual arm does the hard quantitative and qualitative work of living wage research: establishing how much is needed in London and the UK to live on. They “coordinate the announcement of the real Living Wage rates” based on “the best available evidence about living standards”. They provide advice, support, and best practice recommendations to employers that are minded to make the leap to the living wage. Perhaps more nebulously, they exercise influence by facilitating “a forum for leading employers and service providers” to publicly come out for a living wage.

And the annual celebration of the “living wage movement” takes place in November each year in the form of Living Wage week. It is a time for the Foundation to join Living Wage-accredited employers in feting their virtue and commitment to ethical business, highlighting their community credentials and indulging in a well-earnt public relations love-in. It may be saccharine-sweet, but what’s not to like?

Living wages and zombie politics

The answer is, on the face of it, not a huge deal. After all, I didn’t begin this article looking to excoriate the Living Wage Foundation for its efforts. The labour market is a veritable ocean of bad actors, and I’m not inclined to sniff at the work of a generally benign and quite constructive organisation. But we should be aware of its limits, and the limits of the model that it embodies. In that spirit, what are the limits of the living wage model and how should we look beyond it to secure lasting improvements for workers?

The first clue can be discerned in the rhetoric deployed by the foundation to describe its work. The Foundation “recognises the leadership of responsible employers” who “choose to go further” than the government minimum. Even as Living Wage criteria are stated in terms of absolute material poverty – “what people need to live on” – the achievement of Living Wage status is related as a triumph of the employer. This portrayal, which is embodied in the celebrations of Living Wage Week, gently implies that employers are benevolent agents deigning to supply their employees with a livelihood; employees are paid enough to live on as if by the grace of God, not by right. Not only does this miss the mark in various particular cases (anyone who has wrestled with their employer over late or missed pay will know that eventual success is most often not freely given but painstakingly extracted) but it also misrepresents larger historical struggles over pay and conditions. Decent pay, safe conditions, and basic leisure time were won for all by movements of workers, not by gaggles of lobbyists; this is a lesson we can scarcely afford to forget in a time of increasing workplace precarity.

The second big red flag that cannot be ignored arrives through the implicit logic of the Living Wage ‘decision’. For many employers, especially but not exclusively those existing to generate profit, the decision to obtain Living Wage accreditation is a business decision and there must be a business case behind it.

Take the insurance giant Aviva, one of the Foundation’s principal partners. Asked about their decision on the Foundation’s website, a director Stuart Wright explains: “We made this commitment because it is the right thing to do. And because it also makes good business sense. We want to be an employer of choice, which helps us to protect the long-term success of our business.” He wraps up as follows: “Paying the real Living Wage will create a better, stronger and ultimately a more successful company for our customers, our people and the communities we are a part of.”

The strong association of Living Wage accreditation with the business benefits it is supposed to bring demonstrates quite clearly the precarity of the living wage commitment. While Aviva decided to “do the right thing”, their decision depends on supposed benefits that accreditation will bring for the business: it will make them in Wright’s words an “employer of choice” or a competitive employer by comparison with their rivals in the labour market; it will afford them the reputational boon associated with the Living Wage brand. The latter benefit is exactly what the Living Wage Foundation seeks to enforce through its influencing efforts to make their brand a hegemonic indicator of good behaviour among employers.

But the calculus that decides that the Living Wage is in Aviva’s interest – or that of any other business – is entirely contingent on labour market conditions. The incentive to pay competitive wages and not lose employees may be powerful in a tight labour market, but is not so compelling in sectors with a huge reserve army of labour. Reputational damage done by dropping the Living Wage brand is less serious for companies that are further from the public eye. And as soon as these conditions cease to obtain, “doing the right thing” can become untenable for employers with duties to reward shareholders with increasing profits. Rather than setting store by collective power through unions and other bodies, the Living Wage model relies on a coincidence of workers’ and employers’ interests that can only occur in limited circumstances.

Living Wage politics

This Living Wage way of thinking represents not simply an attitudinal difference towards employees – that they are part of our community and deserve to be treated as such – but a brand of Third Way politics that sees bosses’ and workers’ interests as fundamentally resoluble; not locked in intractable struggle, but ultimately on the same team. It is a story of class cooperation for the better of all. And it is a beguiling story, as it is one that allows the listener to abandon political struggle for the technical wrangling of liberal policy influencing. But it is a story without a happy ending, and one that makes any gains for workers fundamentally precarious and contingent on clement labour market conditions. We can see this in the ease with which then chancellor George Osborne co-opted the language of the Living Wage in his 2015 budget with a token rise in the minimum wage and some canny rebranding. We can see it in the enthusiasm with which major employers adopt Living Wage credoes. And we can see it in the disregard it implies for workers abroad, several removes down the supply chain and beyond the dim, strained sight of UK regulators.

Thankfully, it is a brand of politics with less credibility than it has had for a long time. Social movements, campaigns, and trade unions – especially smaller insurgent unions without the institutional tie-ins of their larger counterparts – recognise that workers’ rights are extracted, not just gladly received, through dedicated organising. What’s more, major political parties – such as the Green and Labour parties in the UK – are setting ever more store by strengthened unions and novel forms of workplace democracy. This rather than the liberal model of the living wage model is the future we should strive for. In Living Wage week, let’s recognise the importance of being paid a living wage – but let’s look beyond its limits to real workplace democracy.

Leave a Reply