Learning apart: Northern Ireland’s divisions begin in the classroom

Approximately 90% of Northern Ireland’s school children are in schools that are divided primarily by the religious tradition or community of the pupils that attend. Yet 79% of parents polled in an attitudinal survey in 2013 said they would support their children’s school becoming integrated.

This kind of divide between public opinion and the Northern Ireland Assembly’s decision-making will not be surprising to those who follow Northern Irish politics, but the topic is one that many people outside of Northern Ireland are unaware of.

In Northern Ireland, the vast majority of children are educated separately, based on whether their parents want them to be educated in a traditionally Catholic or Protestant learning environment; the Catholic schools are maintained by the Catholic Church (they are often called “maintained” schools), and the state controls remaining schools in a way that is primarily Protestant (often called “controlled” schools).

At post-primary level, the division becomes even more profound, where students are separated by ability following testing in their final year of primary school into Grammar and High/Secondary Schools, and many schools are also divided by gender as well. This division, in an already deeply divided society, means that children can reach work never having had a chance to make friends with someone from the ‘other’ community, something that means they will more readily believe prejudice and lies about people from outside of their own community. It also means that people who do not feel part of either traditionally Catholic or Protestant communities often have to pick between them to choose where their children will go. The old joke of “but are you a Catholic atheist or a Protestant atheist?” is still very much alive, and a problem for the growing number of people who identify as “Northern Irish” above “British” or “Irish”. It can also be a very big problem for migrants and refugees coming into Northern Ireland who often don’t fit into either community even if they share a religion.

This is where integrated education comes in: integrated schools allow children to all be predominantly educated together as part of one community and taught based on ethics and beliefs that they can all share, while also giving separate space for children to be given some religious education for their family’s religion.

This is something that the Greens fully support and have been connected to for a long time, many Greens in Northern Ireland came through the integrated system, including the Deputy Leader, Clare Bailey who was part of the first class of integrated pupils in Northern Ireland; and those of us who didn’t get to go through the integrated system are often in support of it as a result of our experiences in segregated education.

There is also a purely practical side of things where we have massive duplication (or sextuplication when gender and ability come in at post-primary level) of resources, where there will be multiple small schools in an area, all with their own premises and administration to fund, and potentially all too small to really be viable, but with integration we could merge the expenses at a time when the Assembly are administering massive cuts and maintain education standards.

It was through GPNI’s support and my role as Chair of Young Greens last year that I was able to participate in a report on young people’s opinions of integrated education by the Integrated Education Fund, one of the main groups supporting integrated education in Northern Ireland. The report was launched in September at Stormont in an event sponsored by the Green Party leader, Steven Agnew MLA, and the launch included a panel discussion that I was part of.

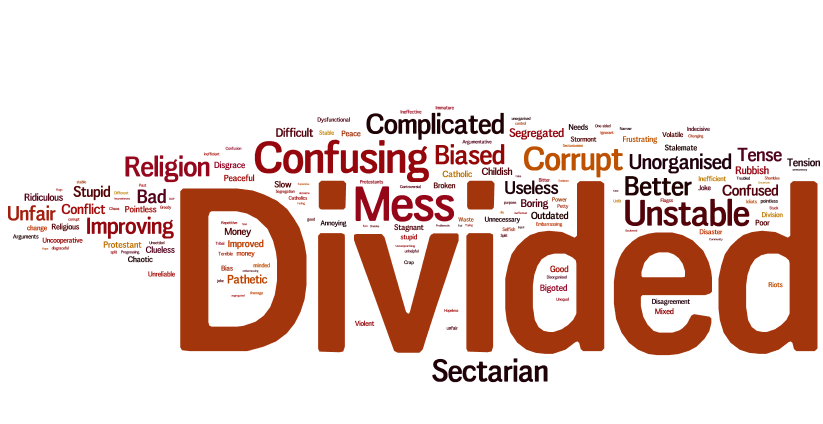

Unsurprisingly, the report showed that there was overwhelming support of integrated education and housing for Northern Ireland, while also sharing some harsh insights about how young people in Northern Ireland view the peace process, insights that are important to pay attention to as many of those asked are part of the “post-conflict generation”, people who are too young to remember the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement.

I highly recommend reading the report in full, as it’s a fascinating bit of work, but it’s evident even from the key findings that young people still feel that Northern Ireland is divided and that education is a massive part of that.

When we have reports every year of young teenagers being arrested in flag or parade-related violence, when we’re fighting a massive brain drain of young people leaving year on year, and when we’re facing awful cuts from the Assembly and the Tories, it only makes sense to take action to make sure our children grow up together rather than growing apart. It’s much harder to hate any group when you sit next to them in a classroom, and a fully integrated education system could shorten the amount of time it would take to erase sectarianism in Northern Ireland by generations.

Leave a Reply