Voice from Vermont: What Murray Bookchin can still teach us about environmentalism

Like any stereotypical twenty-something I feel the compulsion to stay active on social media, browsing Twitter every day or so. Without fail every few days the same command keeps popping up on my feed; “Google Murray Bookchin.”

Who was this Murray Bookchin, and more importantly why do left wing environmentalists keep tweeting about him?

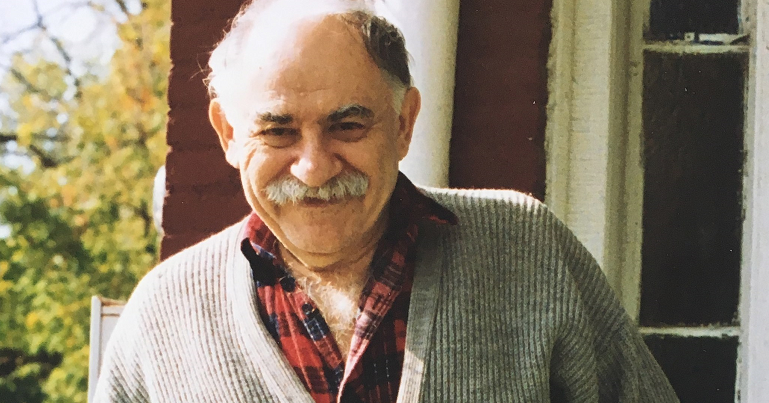

Well, Murray Bookchin was an environmental political activist and thinker in the US in the 20th century. He passed away on July the 30th 2006, 13 years ago this week, having settled for a number of years in Vermont. The founding father of Social Ecology, his thought has inspired many “Occupy Wall Street” activists, as well as partly inspiring the autonomous region of Rojava.

Whilst I don’t necessarily consider myself a follower of Bookchin, his contribution to environmental and political thought really should be more widely known. So, I suppose I do agree with the tweets; one should google Murray Bookchin.

To give a short summary of social ecology, it is the recognition that our environmental crises have their origin in the hierarchies and domination of others within society. Thus, to achieve a green society, we must also have a radical decentralized society, underpinned by direct democracy and a non-hierarchical system.

Listen Marxist, Listen Capitalist

Bookchin was a prolific writer and speaker, with some of his political positions changing throughout his life. Despite this, one of the threads unifying the Bookchin’s thought throughout his life is the demand that all existing social theories were rethought in the face of environmental crises.

Once a member of the Young Communist League, Bookchin was consistently anti-capitalist. But his work also demanded that socialism had to be reconfigured too. His famous essay “Listen, Marxist!” points out a number of problems he identified with leftist politics as they were developing in the late 60s.

Now, there has been a considerable body of work designed to rectify Marx with ecological thought since, most recently with Malm, Moore, and Saito. Whether these attempts are sufficient to refute all of Bookchin’s criticisms likely depends on how sympathetic you are to the existence of a state. Bookchin was highly critical of the centralising tendency of Marxism and felt that this was a barrier to a truly emancipated society.

This demand for new thinking in the face of environmental collapse is not at the cost of all previous thought. Bookchin built on the Marxism he learned in the 30s, the anarchism he was involved in for the next decades, and even utilised the older classical philosophies of the Greek polis in his writing.

His recognition that our environmental problems require us not to discard, but to develop and carve out from existing thought a practice of progressive environmentalism should be reiterated. The scale of the problem of climate change challenges nearly all ways of thinking about society, it is a planetary mirror asking us to reflect.

Often, many greens argue that ecological concerns are neither right nor left, but so distinct as to be separate from established politics. Bookchin rightly rejects this, constructing on past thought rather than discarding everything that has come before.

Bookchin versus deep ecology

In the late 20th Century another key contribution by Bookchin was his debate with the deep ecologists and Earth First! over what he saw as socially reactionary elements of their thought.

For a deep ecologist the cause of environmental problems is human-centred thinking, and once society is eco-centric our environmental problems will be erased. Ultimately, the whole of life has certain minimum rights, which humanity holds no priority over.

But for Bookchin, this kind of thinking flattened “humanity” into one single subject of responsibility, rather than acknowledging the different contributions made by the privileged. Consequently, erasing the fact that environmental problems and social issues are closely linked.

Many deep ecologists had a love affair with population control, and the ideas of Thomas Malthus; a Georgian era thinker who suggested that social problems were caused by overpopulation. Fears of population outgrowing demand led to some deep ecologists like Dave Foreman suggesting that the USA must close all borders to Latin America. More sinisterly Edward Abbey talked of immigration to America threatening to “Latinze” the nation’s culture.

As a result, Bookchin was concerned that deep ecology could lead to xenophobic or racist policies, which could force even more harm onto those already harmed by the effects of environmental collapse.

Many attacked Bookchin for writing so strongly against other environmentalists, arguing that unity was more important to the movement. But Bookchin recognised that calls for comradeship or “broad tent” approaches are trumped by the need for greens to root their environmentalism in respect for people.

As Bookchin himself states in his essay Yes! – Whither Earth First?:

How the Arizona Junta, its “warriors,” and its deep zoologists with bullwhips expect to save wildlife and nature without showing any concern for people is utterly beyond my comprehension.

Bookchin today

Why does any of this matter now? Bookchin died during an atmosphere of scepticism around the possibility of a resurgent left-wing politics. The deep ecology/social ecology debates no longer plague the environmental movement. The world is warmer, the seas are higher, and society has moved on.

But public engagement with issues like the climate crisis are at an all-time high, and there is a general consensus that more needs to be done. To assume that this concern for the environment can only be co-opted by the progressive left is a mistake.

There are significant elements on both the right and left economically who could incorporate care for the environment with socially regressive policy. The lesson of Bookchin is to be vigilant to these elements and refuse to allow them to lead the movement.

In the UK the Conservative Party has attempted to realign itself as sufficiently environmental, as has both the Liberal Democrats and Labour. All these parties have failed significantly in the past to deliver not only socially progressive policies, but also protect the environment. In these times of political uncertainty, environmentalists must be wary of not just how a party votes on emissions, but on the issues of global and social justice as well.

Moving forward

Irrespective of one’s position on social ecology and the writings of Bookchin, the spirit of his movement should be kept alive. Bookchin demanded that greens in whatever form recognised environmental problems’ link with classism, patriarchy, and racism.

I fear now and write often of my concern about a nascent “any means necessary” approach adopted by environmentalists. This attitude can easily slip into the politics of xenophobia, sexism, and ultimately fascistic policies. One reason to read Bookchin is he attempted, no matter how successfully, to be a counterweight to this tendency in the 20th Century. In losing his voice, I fear the balance is slipping away from those of us concerned with delivering actual climate justice.

The voice from Vermont was one steeped in emancipatory politics, and one that demanded we look environmental problems down and practice politics differently. Let’s hope it still echoes.

This article is the first in a series on contemporary environmentalism and the dangers of ecofascism. The series has new articles published weekly, all of which can be found here.

Image credit: Debbie Bookchin, Creative Commons

Thanks for the remembrance of Bookchin.

In the same vein I think: https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/commentary/green-economics-versus-growth-economics

Also, Ivan Illich’s 1972 essays, “Energy and Equity” — http://blogs.ubc.ca/landscapesofenergy/files/2010/11/ivan-illich-energy_and_equity.pdf (“only a ceiling on energy use can lead to social relations that are characterized by high levels of equity. … Participatory democracy postulates low-energy technology.”)