The Labour Party has never lived up to its ‘socialist’ dream

This article is part of a ‘Green vs Labour’ series on Bright Green. Here, Jen Izaakson and Ross Speer reply to James McAsh‘s argument that socialists should work within the Labour Party.

The efforts of the Labour left over the past five years have been huge, but of little avail.

The project of transforming Labour lies in tatters. Despite concerted pressure, the Miliband leadership has duly fallen in to line with the establishment consensus: austerity, privatisation and attacks on immigration. Assaults on its union links, compounded by a secular decline in membership and the crushing of Party democracy, has left Labour sustained only by myth, nostalgia, and an apparent lack of alternatives. The day has long passed when it could be considered a plausible strategy to try and claim the Labour Party for the left.

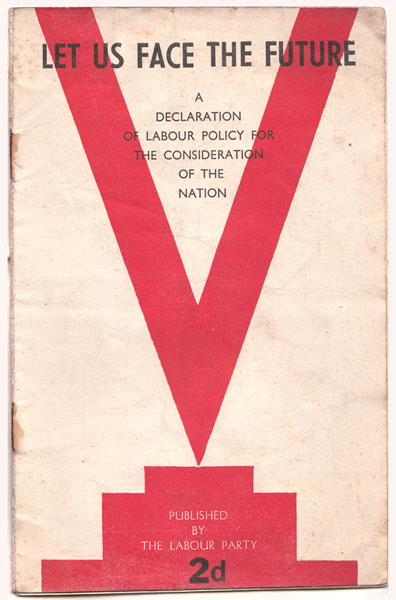

The reality is that the Labour Party has never been the party of the left that our contemporaries sometimes want to believe it to have been. From the Fabians, to Anthony Crosland and the Revisionists of the 1950s and 60s, to the Blairites of today, Labour has always struggled with its identity and purpose: a party of class or a party of nation? Repeatedly, the question has been resolved in favour of the latter. Each time the Labour Party fails to do what socialists suppose it should, and what, at least in the past, it claimed it would do, a left response emerges and seems to make some headway.

Disillusionment with the Wilson governments was met with the rise of Bennism. Anger at Blairism has been partially dissipated by the ‘reclamation’ attempts of Owen Jones, Len McCluskey and others. But with each iteration the challenge from the left becomes weaker, more muted, and less ambitious. Occasional signs of hope, even the odd victory, serve to continue the charade. The trend, however, is in the in the wrong direction. Dogmatic subservience to the Labour Party is dressed up as a clever tactical manoeuvre, yet it owes more to an inability to let go of the past than it does to calculated reason. Their electoral strategy is to obtain the votes of the extra-Labour Party left by moralising and browbeating. With judgement day looming this is the only approach open to them, given that they have no significant record of success to point to inside the Party. But preaching will not cut it this time. We have come to a point at which socialists must take a stand and say they’ve had enough: we will no longer be guilt-tripped into supporting a disgraceful right-wing party just because it entertains some increasingly tenuous links with the trade unions.

The phenomenon of ‘Labourism’ – that dogged obsession with the Labour Party that has beset generations of socialists – is not new. Ever since the ascendancy of the Fabians, the Labour Party has been dominated and led not by the working class, but by a timid reforming intelligentsia. From that point on the Labour left was, as Tom Nairn observed in 1964, “destined to become a left wing permanently, necessarily in rebellion against Fabian mediocrity—but unable to formulate and develop coherently this revolt, intellectually empty, paralysed inside the larger body of Labourism, a permanent minority opposition lacking the resources to assume hegemony of the movement in its turn.” From the outset the Labour left was subordinated to its authoritarian right, and its position has never much moved from there since. At momentary conjunctures it has broken through – 1945, 1960, 1983. Each glimpse proved fleeting.

The transformation of the Labour Party into the B-team of British capitalism, from popular movement to electoral machine, was slow but sure. In accepting the strictures laid out for it by Britain’s business class the Labour Party long ago nullified itself as any sort of threat to corporate interests, and in doing so abolished any possibility of being a vehicle for the left. Its vision of democracy became fundamentally colored by the image of people (‘voters’) loyally trooping out on Election Day, and being quiescent on every other. When they refused, the Labour Party knew which side it was on: and it was not theirs.

What McAsh says he wants is a party of the labour movement. What McAsh has – and will only ever have in the Labour Party – is an instrument well-honed in its task of channeling any dynamism shown by this movement in to the stifling and dangerous conformism of the ballot box. The Labour Party has never lived up the dream, and consequently the term ‘reclamation’ is valuable only for its myth-making qualities, not its accuracy. We are relegated merely to trying to claim it. How many times must we fall before we face the fact that it is unreformable? Reliving past failures is not a demonstration of tactical nous. At some point something has to give, lest we spend the next fifty years caught in the trap that the Labour left has been complicit in creating. Socialists might be solid believers in second chances, but even we cannot be so generous as to provide another fifty years of good graces.

When Labour chose to detach itself from its working class base it also detached itself from any sense of purpose. The Labour Party no longer enjoys deep links with the class that birthed it, and consequently it does not possess the structures that might once have offered the possibility of altering its course. The Labour Party we confront is constructed around an institutional hostility to the left. Nearly always the dominant narrative throughout its history, its worst excesses could, in the past, at least be restrained. The Party’s long civil war resulted in a decisive victory for the right. Perhaps nowhere is this triumph of nation over class presently clearer than in its visceral dismissals of the SNP. In a sorry advance on its spiteful antics in Tower Hamlets, the Labour Party has chosen to effectively dissolve itself north of the border. The refusal to commit to ‘lock David Cameron out of Downing Street’ is now culminating in the increasingly pathetic figure of Douglas Alexander, the Shadow Foreign Secretary and veteran parliamentarian who faces being unseated by 20-year old SNP upstart Mhairi Black. Ed Miliband would sooner unleash the Tories on the people of Scotland then he would cede to the demand of unilateral disarmament, thereby endangering the capacity of the British state to engage in mass murder.

The stock response of an impotent Labour left – when they have anything to say about this at all – is incredulous admonishment that ordinary people would have the cheek to vote for a party other than Labour as and when it becomes available for them to do so. If their complaint that the SNP is also not a socialist party is surely true then it merely serves as a damning indictment of the present state of the Labour Party, that they can be outflanked on the gaping chasm to their left with such breezy effortlessness. Moderate spending increases are hardly the stuff of a socialist wishlist, but the Labour Party has become so immersed in its warped right-wing caricature of reality that even this is barely thinkable from within its ranks. The Labour left has not even managed to propel rail nationalisation – a solidly popular policy by any account – on to the agenda, McAsh’s claim that “baby-steps” have been made on the issue notwithstanding.

What we both want is a socialist party. The Labour left cannot even deliver a social democratic one. When Rachel Reeves is not in full flow, it is almost possible to believe that the Miliband Labour Party has reached the giddy heights of social liberalism. This in spite of apparently favourable conditions for the left, a position of strength, both in terms of raw votes and of Labour’s financial dependence, as well as the election of the trade union backed candidate to the leadership.

It is easy enough, at election time, to tell the principled socialist, for they still exist inside the Labour Party in droves, from the slavish loyalist. The former will be hoping and wishing for Labour to look left to form a coalition after May 7th, however difficult Miliband has now made that task. The latter will spend the next few weeks degenerating in to a series of shrill attacks on the Greens and the nationalist parties, the organisations that have caused them considerable embarrassment by having risen so rapidly from obscurity to put forward the type of program that the Labour left has been unable to present since 1983. The Greens and their allies in Plaid Cymru and the SNP, whatever reservations one might justifiably maintain about these parties, are proof enough that it is now considerably easier to construct a left-wing project from outside the Labour Party than it is within it.

The slavish loyalists may now be lost to us, and will likely choose, whatever the weather, to keep themselves locked in the prison alongside the Blairites. With those that have not let their socialist principles become overridden by appeals to ‘tactics’, we hope that after this election they will plot their exit from the sinking ship and join us in constructing a coalition of the radical left from the remnants of three decades of defeats.

- Jennifer Izaakson is a member of the Green Party and an SNP/Plaid Cymru supporter. Ross Speer is not. The full version of this article can be found here.

- This post is a contribution to our Lab vs. Green series debating which political parties progressive activists should get behind in the 2015 UK election.

The dilemma is that people are fearful of supporting the Greens or other left of centre parties in Labour marginals in case we get something far worse, the Tories. Proportional representation would solve that problem, and perhaps propel Labour to the left in a bid to retain their vote. Unfortunately, PR seems just as remote as Socialism.

Yes, spot on.