Religion is a mixed bag – the crucial task is to sort the good from the bad

Jonathan Bartley is the Green Party Work and Pensions Spokesperson. He is author of ‘Faith and Politics After Christendom’ (Paternoster, 2006) and the founder of the thinktank Ekklesia. He is also standing for selection as the Green candidate for London Mayor. Here, he writes on religion, and the importance of sorting the good from the bad.

This is part of a series we are running on faith and green politics launched with this article. Bright Green would like to invite activists and progressive politicians who are believers to tell us how faith and politics go together in their lives. Write to us at front-desk@project1-hvznj9e2s8.live-website.com.

The chances are you have a picture of my great (times four) grandmother in your pocket.

Her name was Elizabeth Fry and she can be found on the back of the five pound note. A prisoner reformer and Quaker, she was motivated by her religious convictions and a driving force behind tackling the inhumanity of the penal system.

The religious history of the UK of course is not always something to be proud of. It is often a story of injustice, oppression and violence. Mahatma Gandi was spot on when he famously observed: “I like your Christ. I do not like you Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.”

It wasn’t always this way. In the first few centuries, Christians followed their founder more closely. They formed co-operatives, pooling their possessions and giving what they had to the poorest. They stood against the injustice of Rome, with some suggestions that they even sold themselves into slavery, trading their liberty for the freedom of others.

But in the Fourth Century things changed. The canny politician Constantine decided to annex Christianity and make it part of the state. The same Christians who had opposed injustice were now aligned with torture, imprisonment and the waging of war. Their religion began to be shaped by identification with the rich and powerful, rather than those who were oppressed.

Religion is a mixed bag. The crucial task is to sort the good from the bad.

This is one of the reasons I set up the thinktank Ekklesia. A good religious idea can change the world.

When I was working in the House of Commons in the mid-1990s, a letter arrived on my desk from a Christian suggesting a ‘Jubilee’ in the year 2000 – the cancellation of debts in the developing world. It stemmed from his religious convictions, a Jewish idea of freedom from the slavery of unjust debt. A jubilee campaign formed, which became a coalition of aid agencies, churches, unions, and many others. It resulted in the debt of some of the poorest countries being written off. It is now being proposed as a way forward for Greece.

There is a rich and progressive history of religious ideas that still apply today. Restorative justice, non-violence and active peacemaking, and many alternative models of arranging our economic affairs have religious origins.

When I stood against Chuka Umunna in the 2015 general election, several people wanted to know more about why I was “religious”. They were intrigued to know that I had campaigned for LGBTIQ rights in the churches, and that I helped set up the Accord Coalition with the British Humanist Association to end discrimination in faith schools. They were even more interested when they discovered that I had done these things because of my faith, not in spite of it. It was my beliefs that had motivated me to get stuck in.

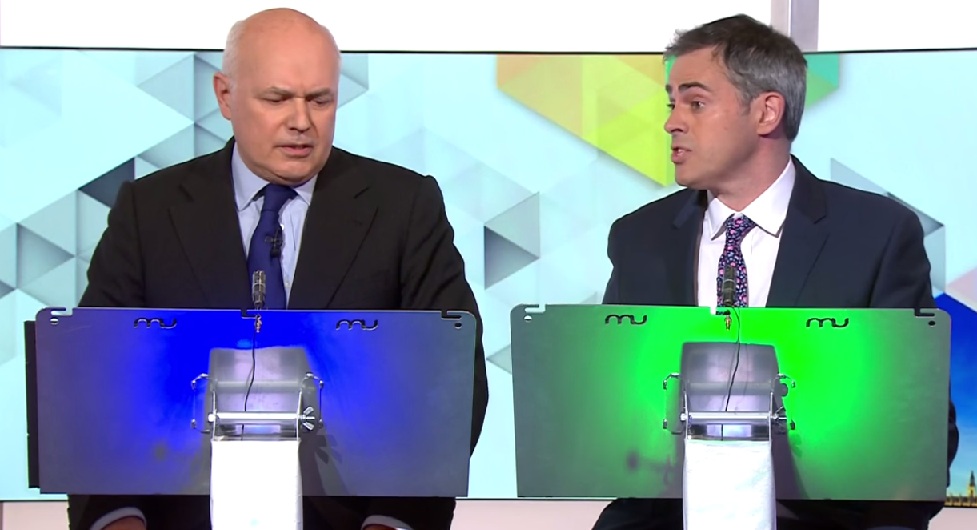

My faith has also led me to challenge bad religion. This is something we did a few days ago, when we organised a critical letter from leading Catholics to Iain Duncan Smith over his welfare reforms. It followed my television debate during the General Election as the Green Party’s Work and Pension’s spokesperson, during which IDS accused me of being a ‘bad Christian’ for challenging him over the suicides of benefit claimants.

I welcome the weakening links between religious institutions and the state. I think it is good for both. I would like to see disestablishment and the removal of bishops from the House of Lords. There should be no privileging of religion or immunity from criticism. A healthy distance between church and government means that the religious are less likely to feel the need to side with the injustice of existing social structures. It also means the churches are freer to challenge the injustice of Governments.

But this does not mean the removal of religion for politics. It means a change in the terms of engagement. Religious ideas should stand or fall on their own merit. And we all lose out if we ignore the good ones.

The whole purpose of a religion is to relieve the faithful of the task of sorting out the good from the bad. So if, as a believer, you feel the urge to sort out the the good from the bad, then you should get out quick. (This advice comes from someone who was taught by Jesuits at an early age.)