As the climate clock strikes midnight it’s time to look to the morning

Climate change will profoundly reshape our world in the coming decades. Yet, in this article, I make a case for why we should not give in to despair and apathy. Turbulent times are upon us, and if we hope to see a new dawn, we will need to be clear-headed and ready to lead the way.

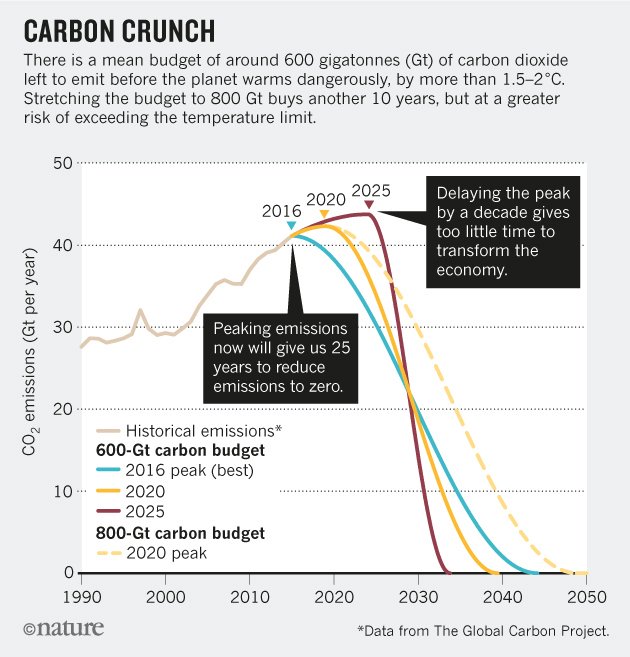

Increasing forest fire activity (Data visualisation by Jill Pelto)

Researching climate change puts me in a position where I often get to talk about it. Sometimes an unsuspecting stranger might throw an innocent “so, what do you do?” at me in an effort to engage in casual conversation before soon regretting when the small talk suddenly takes an awkward gloomy turn. On better days, I might share a cathartic moment with like-minded friends while exploring a topic that, in most circles, still very much feels taboo for its dispiriting potential. Through talking to a wide range of people, I have often been struck by how even highly educated and socially aware individuals who care deeply about doing right by others would sometimes lack a sense of the speed at which our societies would need to change if we are to avoid some of the most catastrophic impacts of climate change. And for good reasons: the future is full of uncertainties and understanding the different scenarios devised by the community of climate scientists requires unpacking a whole load of assumptions. Oh, and then there’s that intuitive reaction of self-maintenance that tends to make you tune out when things start to appear devoid of any hope. Incidentally, several environmental groups and campaigners—in an effort to avoid losing the ear of the public and of the politicians they try to influence—have fallen into the trap of advocating a position that they know all too well would only commit us to insufficient action. But the more we shy away from the sinister implications of climate science and start positioning ourselves as ‘pragmatic’ advocates of gradual progress, the more we contribute to the collective denial that leads most of those around us to believe that banning petrol cars by 2040 or to go carbon-neutral by 2050 is what ambitious climate action is supposed to look like.1

In this article, I want to take some of the most unsavoury bits of climate science and try to make them digestible to a large readership by unpacking the assumptions that muddle the translation of science into action at every step. Yet, I am also aware of the risk that dropping more doom and gloom on unsupported readers may not lead to more engagement, but to apathy or even trauma, which is why I also want to offer some of my own reflections on the implications of such projections for the actions that we take in the coming years. “It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society,” the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti so well puts it, and part of how we will build the world of tomorrow is through rekindling networks of support for those struggling to hold on to their sanity in these strange times. Think of it like an extended hand to join a community refusing to surrender in the face of a crime that has for too long been presented as a tragedy.

Where we stand today

Perhaps a good place to start our journey into the assumptions that lie behind climate predictions is the internationally agreed target of 2°C. What we first need to understand is that 2°C—as the level of additional warming that has been deemed as acceptable by the international community—is a somewhat arbitrary target defined on the basis of political acceptability rather than scientific considerations. The temperature target was first mentioned in a 1990 report by the Stockholm Environment Institute as an absolute upper limit for avoiding the worst impacts of climate change.2 Yet, despite the report’s warning that any additional warming beyond 1°C could elicit rapid, unpredictable and non-linear disruptions to the atmospheric system, the 2°C limit was taken up by the European Union as a policy target under the justification that it supposedly corresponded to the point at which the cost of reducing emissions would be outweighed by economic losses incurred due to climatic disruptions. Although the scientific community never actually supported the 2°C limit, the political salience that such a target enjoyed for seeming both realistically achievable and tolerable within the constraints of an economic system hooked on fossil fuels meant that it gradually imposed itself as a rallying cry for the entire climate community. Politicians are now expected to implement policies in line with this target, science and industry have been repurposed to try to find ways to make mitigation less costly, and environmental activists are now constrained to hold their governments accountable when they do not even stick to their mediocre promises.

A number of key tipping points already risk being triggered by a 2°C warming

(Source: www.climateactiontracker.org Ecofys/Climate Analytics/PIK)

Now that we have cleared up that 2°C as a goal is neither morally nor scientifically defensible, let’s play along with it anyway. Since the whole world has collectively agreed on a mad target, arguing from a position of sanity can be both isolating and futile, for you can be sure that it will be discarded as either naïve idealism or dangerous radicalism. Instead, we shall meet the crazies halfway and demonstrate the insanity of their logic by following it to its conclusion.

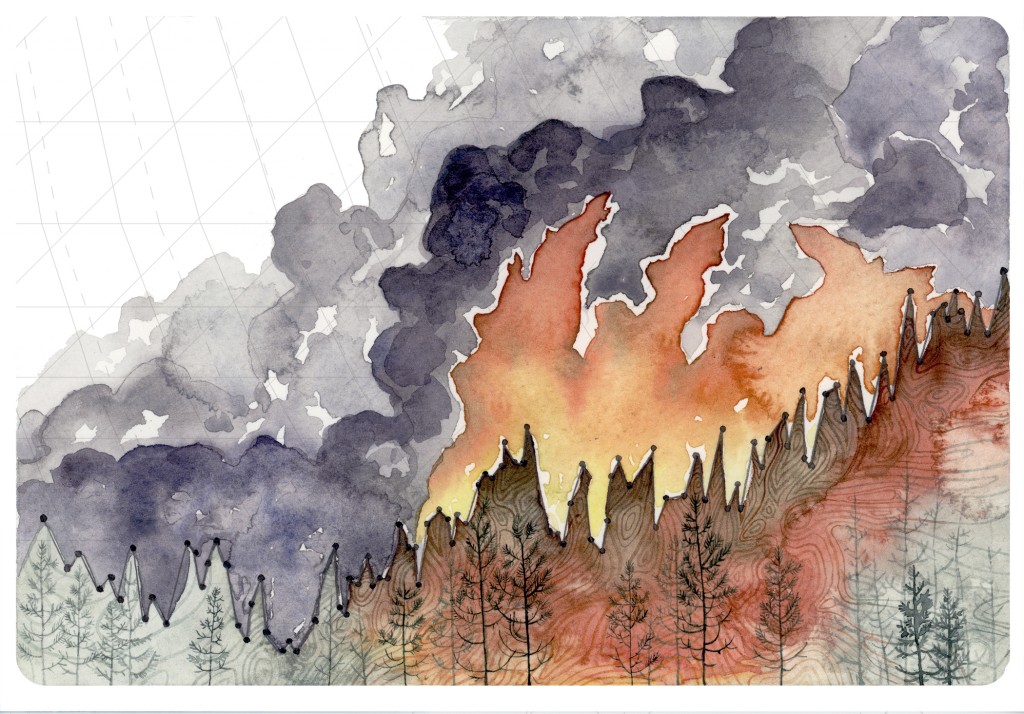

Now that all of the world’s leaders agreed, after 25 years of procrastination, to limit the rise of temperature to 2°C as part of the Paris Agreement (well, all leaders except now Trump, but let’s just leave that buffoon aside for now), we at least have a concrete figure to work with. When translated into a measurable amount of CO2, 2°C means that no more than 600Gt can still be emitted for a >66 percent chance of not exceeding this temperature threshold. This figure—known as our global carbon budget—can vary depending on the amount of risk that we are willing to take with how much we destabilise our atmosphere. As such, rare are the governments that actually base their policies on the budget offering a >66 percent chance, and most contend with a mere 50/50 chance while some—including the United Kingdom and the European Union as a whole3—even go as low as betting everything on a 33 percent chance (the corresponding carbon budgets respectively expanding to 900 and 1100 Gt).

Here I want to briefly interrupt this analysis, and reflect on what these numbers actually mean. By framing risks in terms of probabilities to meet or to miss a target, it is easy to lose touch of what hides behind such technocratic exercise. That our governments are willingly basing their policies on the riskier pathways should in itself constitute a crime against humanity, but perhaps we should also be asking: In what world does a >66 percent chance even constitutes tolerable uncertainty? If the bar for the aviation industry was set so low that planes had only a two-third chance of making it safely to their destination, I bet that none of us would ever risk to fly. And yet, these are the best odds on which we are now gambling the life-support system of our entire species.

Where we are heading

With this perspective in mind, let’s dig deeper into those budgets and uncover the next layer of inadequacies in our current approach to tackling climate change: the issue of how we divide up carbon budgets across time. Because the CO2 that we add to the atmosphere remains there for hundreds of years to millennia, carbon budgets are essentially a finite, non-renewing resource. The 600Gt budget mentioned above is not just what we have today, but what humanity will have to make do with from 2017 until the end of its passage on Earth. To get an idea of what this means for our near future, this number should be put in perspective with our annual rate of emissions, which amounts to 40Gt a year from industrial processes alone (and therefore excluding land-use change induced by agriculture or extraordinary events such as wildfires). It doesn’t take a science degree to divide one by the other and to realise that at the current rate, it would only take a meagre 15 years to blow our chance at 2°C. The challenge, therefore, is that our emissions should immediately stop rising and be reduced drastically during the next decade so as to remove every form of CO2 generation somewhere between 2030 and 2040.

What the next decades have to look like to stay under 2°C

What the next decades have to look like to stay under 2°C

(Source: Stefan Rahmstorf/Global Carbon Project; http://go.nature.com/2RCPCRU)

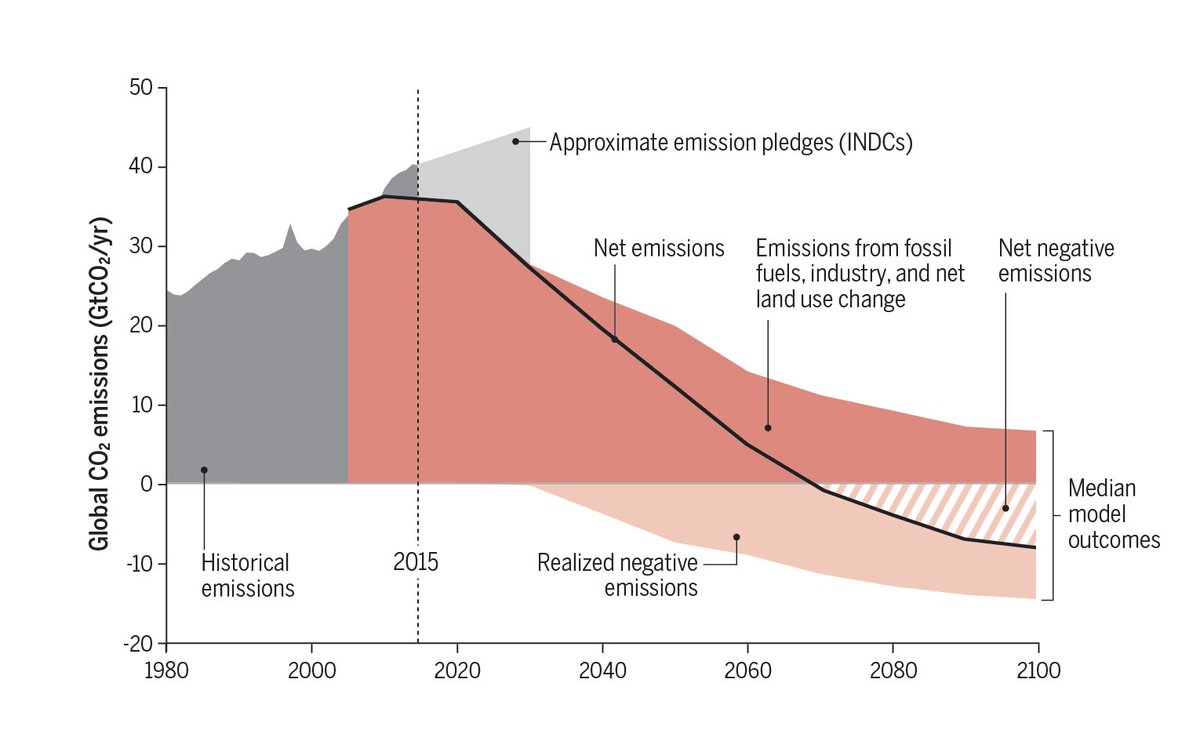

Needless to say, current ambitions take us nowhere near that path. Instead, unpacking the implications of our governments’ plans to achieve what they have promised reveals yet another world of disquieting ambiguities. Indeed, while you might assume that the threat of near-term extinction would prompt a questioning of the dominant economic logic that restricts the realm of possible actions, that failed logic managed to be maintained thanks to a cunning new trick: the fabrication of the concept of negative emissions, of which the reasoning is clearly illustrated by the graph below. By resorting to the assumption that technologies that can absorb carbon from the air will be developed later this century, the narrow margin of manoeuvre of the 600Gt carbon budget is then artificially extended—at least in principle.

Negative emissions realised in the future underlie our present lack of ambition

(Source: Glen Peters and Kevin Anderson; http://science.sciencemag.org/content/354/6309/182)

While the pace of transition certainly looks less alarming when able to be stretched all the way to 2100, this false sense of comfort should be offset by the fact that we currently have no idea of how such negative emissions might be delivered. As of today, all hopes seem to be invested in what is known as Carbon Capture and Storage technology (CCS) combined with a massive uptake in bioenergy consumption (the combination of the two usually nicknamed BECCS). In other words, our refusal to act in the present is compensated by a gamble on the fact that we will be able to burn lots of trees (which absorb CO2 as they grow), stick a device on our chimneys to capture all the CO2 emitted during their combustion and inject that gas under the ground where we hope it will remain trapped for eternity.

If the track record of Carbon Capture and Storage technology is already mixed at best, the truly unsettling aspect of the whole process relates to the scale at which it is presumed to be deployed. Indeed, assumptions about the biomass use anticipated to deliver the negative emission rates taken for granted in these models are almost farcical. For one thing, the European Union, which currently supplies a mere 5 percent of its energy demand with biomass is already relying on imports and triggering intensified logging outside of its borders.4 With our scenarios relying on between 10Gt and 20Gt of yearly negative emissions to come from BECCS by 2100 (one quarter to half of what the global economy currently emits), it is estimated that land equivalent to one to three times the surface of India would be required to grow the corresponding amount of biofuels.5 In the context of increased droughts, food shortages and wildfire that climate change is set to bring, serious doubts can be raised on the practicality of deploying those measures in the real world. Similarly, when considering that about forty kilograms of CO2 are emitted for every kilogram of solid waste that we dump into our landfills—and that we already struggle to find enough space to dispose of this waste—we hardly see how finding enough leak-proof subterranean cavities to contain all the carbon dioxide needing to be captured by CCS technology can appear like a reasonable assumption.6

But let’s just assume that I am being overly cynical about what can reasonably be expected from technological progress. Who knows? Maybe we will, after all, figure out a way to make all the carbon magically disappear at the flick of a wand. The problem, however, is that if no one can give definite proof that technology will not be our saviour, the paths that we are choosing today are assuming with certainty that it will. Blind faith in our future ability to bury carbon on a planetary scale now underpins all of our actions to mitigate climate change.

The path not considered

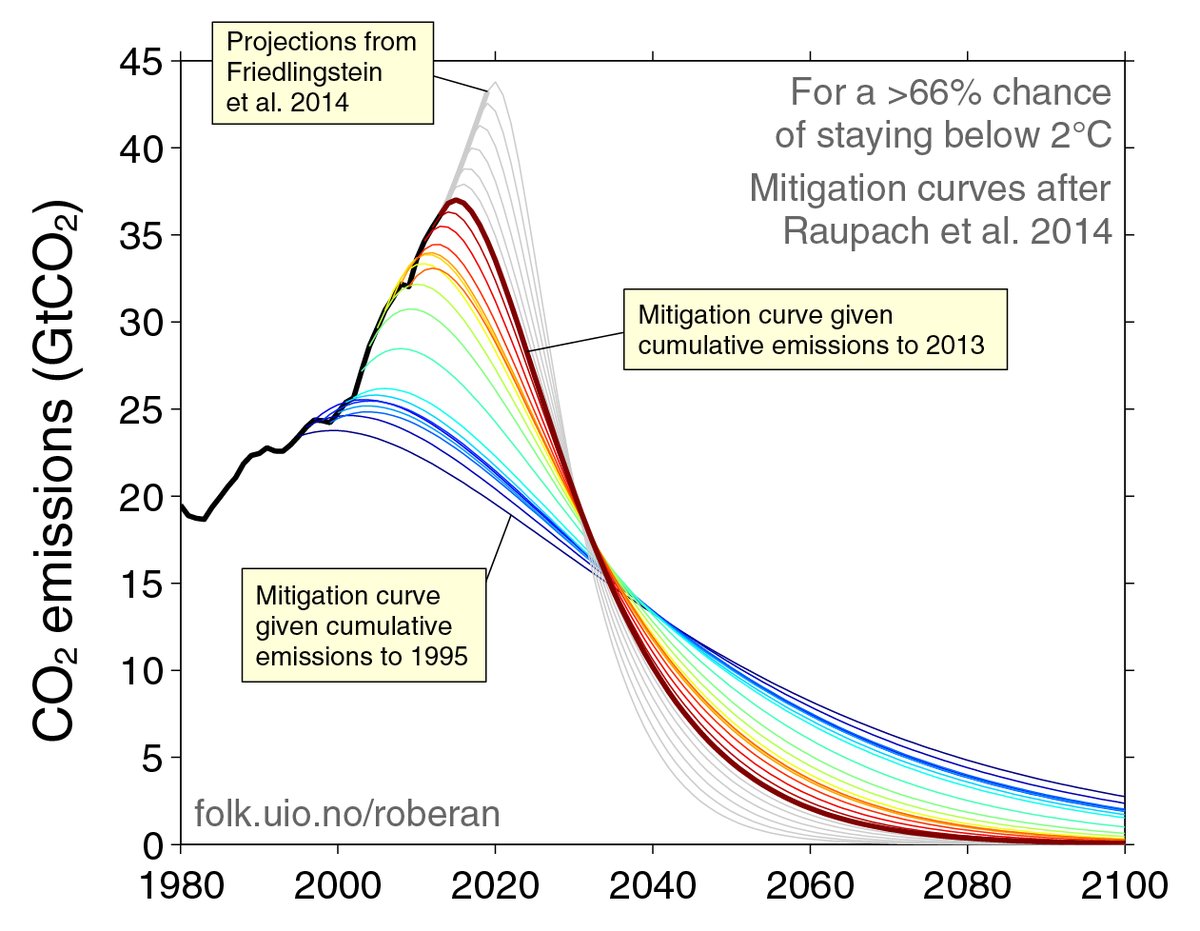

The most pernicious effect that these hopes in technological salvation have is the very tangible delays that they inflict on the present. For each year of delayed action, the rate of the change needed becomes even more rapid, making our reliance on BECCS seeming even more and more like the only pragmatic option.

Even scenarios that take BECCS for granted will soon require drastic emission cuts

(Source: Robbie Andrew; http://folk.uio.no/roberan/t/global_mitigation_curves.shtml)

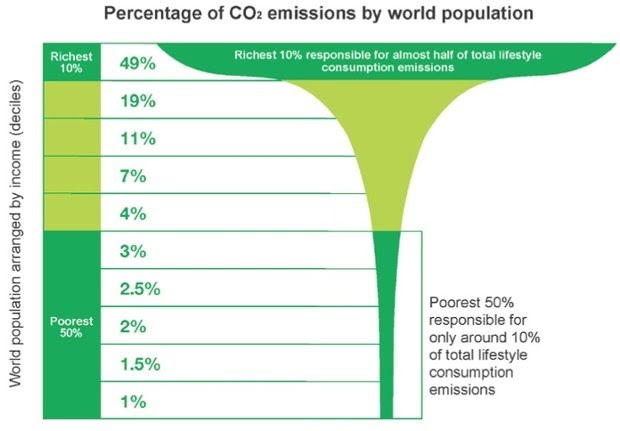

Yet, there is actually another way to get emissions down fast enough without having to gamble everything on providential technological fixes. What is more is that given what we know about the alternative that I just described, there is no compelling argument why such a plan wouldn’t seem immensely desirable to the vast majority of people. To get emissions to fall at the speed required by our very limiting carbon budget, we must turn our attention to where—and most importantly who—they are coming from. Indeed, by failing to recognise the fact that the lifestyle of the richest 10 percent is responsible for half of all global emissions or that the poorest 50 percent only emits a mere 10 percent of it, the idea that climate change is an unfortunate consequence of our inevitable day-to-day activity will restrict our search for solutions.

The lifestyle of the rich is responsible for the lion’s share of our self-destructive endeavour

(Source: Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty/Oxfam; https://oxf.am/2t8gtGH)

Although individuals belonging to the top 10 percent class can be found on all continents—often well isolated from the life experienced by most of their fellow citizens—they tend to be so widespread in North America and Europe that the characteristics of their lifestyle have come to define local cultures and are very rarely recognised as the idiosyncrasies they in fact are. Indeed, while only 7 percent of Latin Americans, 4 percent of Chinese and 1 percent of Indians and Africans belong to the top 10 percent of global emitters, as many as 60 percent of North Americans and 30 percent of Europeans are reported to emit more than 15 tons of CO2 a year—the threshold at which one begins to earn top-10-percent status.7 A couple of long-haul flights a year, daily car usage, regular shopping sprees and a meaty diet—lifestyle habits that can appear so commonplace in the western world—and even you, well-meaning reader of this article, can realise that you are part of the exclusive club of those responsible for the lion’s share of ecological destruction.

Focusing on individual lifestyle changes is often seen as unhelpful by those who make a structural critique of environmental degradation. Yet, is there possibly a structure more pervasive than that which makes the culture of the dominant group seem so mundane? Is the normalisation of highly destructive habits not something to be called out and resisted? By putting the focus on what makes the lifestyle of the rich so much more harmful than the way the majority of the human population lives and by dispossessing those activities of the prestige they enjoy, they will cease to be aspirations for the rest of us. Only then might we be able to achieve the sudden turnaround in emissions that is needed to ensure our survival. Moreover, in comparison with bets on technological progress that ignore all questions of equity, such drastic emission-cuts could be achieved relatively pain-free, since, indeed—besides having to content with some grumpy rich folks—the bulk of the burden would be shouldered by those who are already in a position of obsene privilege.

The idea that human well-being necessarily comes at the cost of our environment is a distinct fallacy of those who only know a life of disconnect from it. This fallacy is so prevalent in our modern societies that a great deal of radical imagination is now needed to reawaken to the fact that lives need not be lived in consumer ways, but can also be oriented towards regenerative purposes. Our most urgent challenge is now to incite restorative vocations while discrediting life pursuits that worsen our predicament. Understanding what characterises the lifestyle of the 10 percent—its practices, but also its ideology—not only opens new pragmatic avenues to achieve fast emission-cuts, highlighting what makes it inherently immoral will also play a part in formulating new narratives of what ought to constitute an honourable life in our new climatically-changed world.

A call to heroism

Making conscious efforts to take a deep dive into the existential crisis we find ourselves in can take you on a roller-coaster of psychological trauma. The realisation of the sheer inadequacy of the measures taken to prevent our Earth from spinning out of control in the coming years is enough for the most hardened among us to shut down and start thinking about escape. And who could really blame you for it? Why investing all these efforts in making a better future for ourselves when our rational mind knows too well that all of this is set to be trampled by the incompetence of those who really run the world? Well, all of that may be true, and I will not have the dishonesty to tell you otherwise. But recognising hard truths will only lead on a path to depression if we lose sight of the fact that there is still a worthy battle to be fought. Meeting the incredibly strict deadline imposed by climate change will require nothing short of a dramatic shift in how we think the human experience, our measures of success and our idea of a life well lived. Holidays to far-away locations, luxurious possessions and ever so frequent splurges—the defining elements of ‘the good life’ as experienced by the 10 percent— are indefensible with a moral compass tuned in to the logic of climate change. On the other hand, earth-regenerative acts, conscious sobriety, community rekindling and active opposition to destructive forces can provide us with what the old world and its promises constantly failed to provide: a life mission, a sense of belonging, and a great source of fulfilment. If we are to collectively survive this century, we will have to embrace our identity as agents of change; as protectors and stewards; as champions of a humanity tuned in to its better nature. The climate change era is already upon us, but let it not be an era solely marked by death and destruction. Let’s invest our whole hearts, soul and strength into an era of bravery, kindness and imagination.

References

1 Michael Hoexter, ‘Living in the Web of Soft Climate Denial’, New Economic Perspectives (7 September 2016), http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2016/09/living-web-soft-climate-denial.html.

2 Carbon Brief, ‘Two degrees: The history of climate change’s speed limit’ (12 August 2014), https://www.carbonbrief.org/two-degrees-the-history-of-climate-changes-speed-limit

3 Kevin Anderson and Alice Bows, ‘A New Paradigm for Climate Change: Why Carbon Prices Can’t Deliver the 2C Target’, Nature Climate Change 2, no. 9 (28 August 2012): p. 639–40, doi:10.1038/nclimate1646.

4 Fred Pearce, ‘Up in Flames: How Biomass Burning Wrecks Europe’s Forests’, FERN (November 2015): p.12, http://www.fern.org/sites/fern.org/files/upinflames_internet.pdf.

5 Pete Smith et al., ‘Biophysical and Economic Limits to Negative CO2 Emissions’, Nature Climate Change 6, no. 1 (January 2016): p. 47, http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v6/n1/full/nclimate2870.html.

6 Andy Skuce, ‘Talking Trash on Emissions’ (7 January 2014), https://www.skepticalscience.com/behind_the_Lines_CO2_shotput.html

7 Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty, ‘Carbon and Inequality: From Kyoto to Paris’, Paris School of Economics (3 November 2015): p.36 and p.47, http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/ChancelPiketty2015.pdf.

Thanks for this article. I came to it by way of a critique in the Financial Times.

I’m part of a lobbying group that started in the US and is – believe it or not – gaining much traction with a bi-partisan congressional caucus https://citizensclimatelobby.org/climate-solutions-caucus/

We are lobbying for a Climate Fee and Dividend, where fossil fuels are charged a steadily rising fee when they are extracted, etc or brought into the country. The money taken is then divided equally between UK households.

The purpose of this is to raise the price of fossil fuels so clean energy alternatives are cheaper, and give a clear signal to the market to invest more heavily in new technology.

The beauty of this is that it works within our economic system, financially benefits households with the lowest carbon footprint (ie to low to middle income families) and doesn’t require people to wear hair shirts.

Best of all – as shown by Canada’s British Columbia who already ready have carbon pricing – it will bring down carbon dioxide emissions.

Although individual effort is still important, we can’t rely on people’s good nature to halt climate change, especially when the alternatives are more expensive or impractical. We need effective legislation.

If you want to support this idea, write to your MP and ask them to talk to Claire Perry the Climate Minister about Carbon Fee and Dividend.

And tell everyone you know – this solution seems little known in the UK.

Here is the US site https://citizensclimatelobby.org

And the UK site (work in progress) http://citizensclimatelobby.uk

Despite living simply and cheaply since the sixties with the smallest carbon footprint possible in this comsuming society, I’m not impressed with optimism that says it’s not to late to make a difference, not to late to avert disaster, but I rejec t the homo centric view that accepta nce of this will lead to depression and worse. I’m OK with the likely fate of homo sapiens, we were an unsustainable experiemnt by evolution in increased animal intelligenc e3 and we seem to have failed the test miserably. All my life as I have treated the planet with respect and valued all other spec ies, most of huma nity has been engaged in personal gain and the inevitable destruction, and all we get is we must preserve the Earth for our children’s children etc. as if humans have some right to the planet, that it is ‘our world’ just because we evolved a bigger brain instead ofg a long neck or any other useful evolutionary change.

It will take a lon g timre for Earth to recover from our selfishness and greed. I take comfort from the thought of a new born Earth free of all we stand for, including our self-serving religious fantasies and determined homocentricity. A truly superior species worthy of the position of top predator would be mindful of all others and their place within the beautiful complexity of the planetary ecology that we have not been a part of for a long time. It will be a virus does the balancing, despite our arrogance we are not immune to evolution. The only possible alternative would be a lifeless planet covered in concrete and tarmac, we will never stop until we are stopped.

Mr. Munsch,

I’d like to congratulate you on researching this topic and driving into solutions both more deeply than typical authors and even major organizations do. Kudos.

However, is also like to suggest that you also stopped just short of seeing the bigger picture which yet more research would have let to. It seems you are a bit shy on your vision for the near term of technological progress.

Technical solutions aren’t some simple choice that can be simply turned to or away from at once. They are a prices involving many steps that take unavoidable time periods. First, there needs to be awareness of a problem. Them there needs to come into existence a vision. Then an idea. Then a viable solution, then some test, design, funding and failure iterations will be needed. Then a commercial solution will need to coalesce from the hodge-podge of possibilities and then finally, a significant mix of funding and market demand needs to present itself in a business friendly form.

This process takes time, lots of time, and the majority of it is usually done behind guarded doors. As such, the public awareness only see the final stages and this underestimated their collective progress. This is the category you likely reside in, along with 99.95% of the general population.

As someone not blinded by this limitation, I’d like to offer a tiny peek at the top of the iceberg-vision into this world. Basically, the following is only the top solutions that are set to become status quo in the next decade.

Before ten years passes, you’re likely to see solar energy systems for a home, business and big box store supply all forms of demand – electricity, heat, cooling and even water – for costs of a quarter to a third of today’s cost.

You’ll see transportation morph into massive abundance. It’ll cost less that a tenth of today, and likely much less, while also using twenty times less energy and resources. Compared to a car trip across the country, it will lose 99% of it’s resource use.

You’ll see a higher meat content diet becoming the norm because the very process of increasing production will soon become a large carbon sink, fixing a significant portion of carbon budget by itself.

You’ll see the monopoly system of mono-crop farming be replaced with massive yield indoor grow farms and the pastures of old returning across the plains.

You’ll see daily commutes to useless fluff jobs be replaced by schedules of sporting and craft activities, paid for by societal development dividends if they even cost at all.

You’ll see ubiquitous power, connectivity, information, communications monopolies being replaced by stand alone equipment that’s paid off in half a decade. Like other ‘self solutions’, this will then yield it’s functions to the owner for up to fifty times the loan period.

You’ll see health being managed by apps that swap reactive care for preventative care and when you do get sick, you’ll have custom drug created just for the ailment. And ultimately robotic precision physical procedures costing virtually nothing since the work for free will handle the majority of repetitive procedures.

You’ll see the education infrastructure replaced by a trend of continual learning built into your smart device that you already carry around now. This device will recognize every opportunity to teach you something on any topic you’ve shown an interest in while you go about your day off leisure and adventure. Also free.

You’ll see manufacturing automation to the level that a simple iterative Q&A session can lead to the full physical creation of any invention you want to dream up. Again at virtually no cost, which will begin to apply to the great masses of consumer products.

You’ll see water created on site for most people but you’ll also see the vast pipelines of today’s world converted to sending fresh water inland from the oceans, again at no cost or resource / carbon expense. This will likely be a free byproduct of another process.

You’ll see the most creative of dwellings being created from simple automation and carbon sinking materials in rapid time and at unheard-of low costs.

Every single one of these and many more are now in development behind some black, locked door just waiting for the Stars to align when they will be sprung on the world. They’re all viable technically but currently held up by the mismatch between funds available to no-name inventors and what’s needed to move to the next level.

So if you want to write an insightful piece, try looking into how to accommodate the 99.9% of innovators that have no hope of a connection to the silicon valley regions that have hijacked the global investment world. Try writing about how the vast majority of global warming fear budget is being militantly spent on awareness campaigns, not development. Try writing on the problem that all levels of investment in society now defer to the ones above it, ultimately leading to those top investors who only see “maximize profits” as they’re goal, thus killing the possibility of these technologies ever becoming the cheap or free solution they we’re designed as. Or you could try writing on how a potentially great solution to finding – namely crowd funding – has become a global popularity contest, siphoning even more investment from the highly technical and disruptive solutions.

Now ask yourself what the curve in your graph would look like if all these innovations were already available ten years ago.

Todd, I think more realistic assessment of energy and engineering would help both your points and our decision making.

Note the work of two brilliant inventors:

Saul Griffith:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/05/17/the-inventors-dilemma

http://longnow.org/seminars/02015/sep/21/infrastructure-and-climate-change/

David MacKay:

http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/371/1996/20110431

https://www.withouthotair.com/c19/page_114.shtml

http://globalcalculator.org/

Renewables are constrained by area (as MacKay and Griffith point out) and by intermittency. It doesn’t mean they can’t provide society power, but it does mean it’s not easy, and as Richard Heinberg points out, won’t mean we can use energy as profligately as the West does today.

ecowatch.com/heres-how-we-get-to-100-renewable-energy-1891172891.html

Amen. I quit my job twelve years ago for exactly this reason. Everyone sees there’s a huge problem, nobody knows what to do about it, and if we don’t figure it out it’s ecocide and the end of pretty much everything that any of us care about… So I decided to learn to live very cheaply for a while to give myself some time to think about it. As it turns out, I’ve been living that way ever since, and never been happier – as you say “a life mission, a sense of belonging, and a great source of fulfilment” beats anything the marketing industry offers, by a long chalk.

I think Wendell Berry put it best:

“Protest that endures, I think, is moved by a hope far more modest than that of public success, namely, the hope of preserving qualities in one’s own heart and spirit that would be destroyed by acquiescence.”

If of interest, I feel the most worthwhile thing I’ve done to date is bring the late David Fleming’s “Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy” to posthumous publication. It lays out the most positive, grounded vision of our future I’ve found, given where we are. And makes clear what we can do now in a way where every step feels like an enjoyable step into a more nourishing future, just as you say, rather than toil and sacrifice.

If you’re interested, email me your address and I’d be happy to drop you a copy:

http://www.flemingpolicycentre.org.uk/lean-logic-surviving-the-future/

Best,

Shaun