A better future for transport after the pandemic?

The government is worried that as the economy recovers this year, “the move away from public transport during the crisis will cause unmanageable levels of car traffic, slowing some areas to a crawl”. They are right to be worried. By late September national traffic volumes had returned to their usual levels despite half the workforce working from home. The quote above comes from Bus Back Better, a new policy that aims to encourage people back onto buses to avoid that descent into gridlock. One of the problems, they rightly identify, is that public transport has been getting steadily more expensive. They are promising to make buses (but not rail) more affordable, to break a “cycle of decline”, which they and their predecessors have presided over since the 1980s.

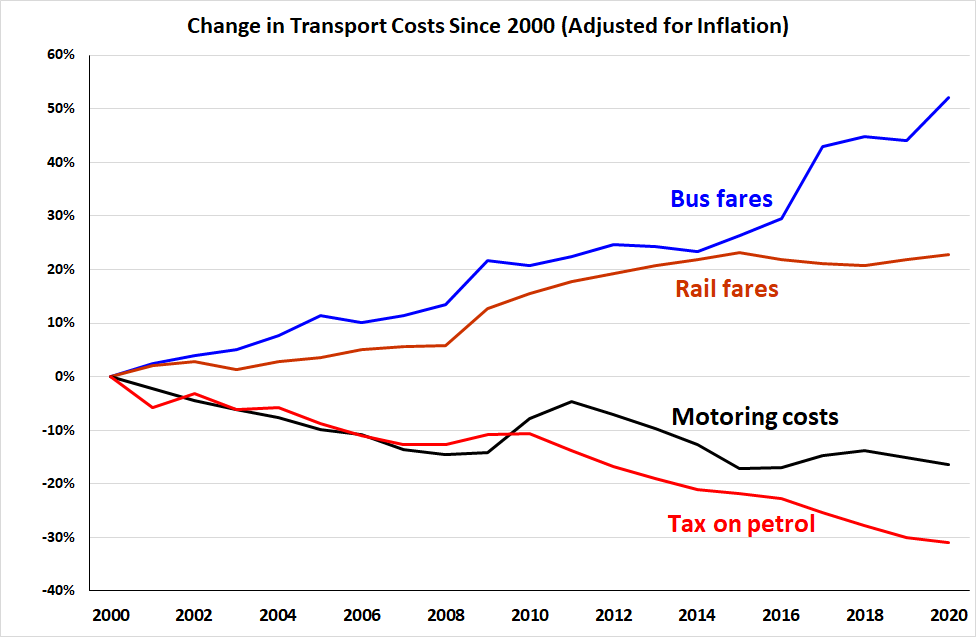

The graph above shows how the problem has worsened since the start of this century. It also illustrates a fundamental problem with their strategy, one which is undermining their response to climate change, as well as urban congestion. As I describe in my recent book, the wave of protests by farmers and hauliers, which briefly shut the nation down in 2000, had a bigger impact in the long-term than it did at the time. Since 2000, governments – and oppositions – have never wavered in their determination to make private motoring ever cheaper. Taxes on petrol and diesel have been cut by a third since then, adding to cost-cutting by the motor industry, which has made driving more affordable than it has ever been. From that trend, there is to be no respite. In the recent budget, the Chancellor cut fuel taxes yet again – because of the way fuel duty is set in pence per litre, what the media calls a “freeze” is really a cut.

If congestion is the big concern, then getting more people onto public transport is unlikely to make much difference in any case. Across the UK, people travel 20 times as far by car as they do by bus, and, as I explain in Urban Transport Without the Hot Air, better or cheaper public transport tends to increase travel more than it reduces driving. Working from home does not make much difference to traffic, either. Commuting only accounts for one journey in six, and working from home tends to increase other forms of travel – including the distances that people live from their place of work. It might change the times and spatial patterns of travel, but anything that removes a vehicle from the roads frees a space for another to take its place. So a permanent increase in flexible working is not going to solve the problem for us.

If politicians and the public really wanted to tackle congestion (and it is not clear how many do) they would have to agree a system that constrains people’s ability to drive. For many transport planners and academics, the answer is simple: road pricing, with higher prices when roads are congested and lower prices at other times and places. The Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, has reportedly expressed interest in the idea to replace fuel duty as electric power gradually replaces fossil fuels. The Transport Committee of the House of Commons is conducting an inquiry into Zero Carbon Vehicles and Road Pricing, to which I recently submitted written evidence.

In theory, road pricing could reduce congestion, traffic volumes and carbon emissions from transport. The devil is in the politics, however. If road pricing were to make motoring more expensive overall, it could achieve all of those things, but any government introducing such a controversial measure would almost certainly cut fuel taxes to compensate. If road pricing made driving more expensive in congested places and cheaper in places with space for more traffic the net result would be more driving and higher emissions.

The other key factor in the fight against carbon emissions from transport, is electric vehicles. Like them or loathe them (and they are no panacea) we cannot achieve zero emissions without them. All of the good things we might prefer – localised living, carfree cities, walking, cycling and better public transport will not get us to net zero on their own. The Sixth Carbon Budget recently published by the Climate Change Committee requires the UK to cut its transport emissions by 70% by the mid-2030s. That is an enormous challenge, which will need rapid electrification as well as big cuts in traffic volumes. To achieve both aims together, we would need to make petrol and diesel vehicles progressively more expensive to use, until they are phased out altogether. Unfortunately governments, encouraged by the media and much of the voting public, have been doing the opposite. Concern for poor motorists – which is the usual pretext – clearly does not apply to bus users, who are, on average, much poorer than motorists. The issue is one of political weight, not ability to pay.

Financial penalties designed to cut the use of something are always problematic. Experimental research has shown that when money is mentioned people become more selfish, less willing to make sacrifice for a common good. If a majority is unwilling to vote for more expensive motoring, then how else could we stem the rising tide of traffic? Restricting greenfield building and housing more people in denser urban areas (with little space for parking) can help. On that issue, governments have also behaved inconsistently. We can reallocate urban road space to cyclists, pedestrians and buses – as the government has signaled in Bus Back Better. We could improve the rail network in lots of smaller, less expensive ways than HS2.

None of that will make much difference to congestion, unfortunately (neither would road building or any of the other demands of the motoring lobby). But is congestion the real problem? Transport is now the largest emitting sector – responsible for a third of UK carbon emissions. Tackling that existential threat is the most urgent challenge. If carfree neighbourhoods are the ideal solution, the reality may include growing queues of stationary electric vehicles. At least they won’t pollute the neighbourhoods they are standing in.

Steve Melia is a Senior Lecturer in transport and planning at the University of the West of England. His latest book, Roads Runways and Resistance – from the Newbury Bypass to Extinction Rebellion, is published by Pluto Press.

PS. We hope you enjoyed this article. Bright Green has got big plans for the future to publish many more articles like this. You can help make that happen. Please donate to Bright Green now.

PPS. Bright Green has an exciting series of events coming up. Join us for debates, interviews and much more.

Image credit: Felix O – Creative Commons

Shouldn’t the tax on petrol line on the graph be labelled fuel duty, not tax? The tax (VAT) is applied as a flat percentage of the price, so it can’t be adjusted for inflation.

No. If you follow the link to the data source, you will see that it shows both the duty and a snapshot of the VAT in the April of each year, expressed in pence per litre. That amount plus the duty then give total tax in pence per litre, which means that they can both be indexed for inflation.

Hey, well done Dave for proving DrMelia is correct. I’m impressed by your subtle genius.

If petrol tax has been flat at 58p since 2011 whilst inflation has devalued buying power then it really does mean tax has dropped in real terms.

If the 58p had maintained pace with inflation it would now be 72.29p, but it’s not.

You can check it out on the BoE inflation calculator

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

BTW, the graph doesn’t stat petrol tax has dropped 30% from 2011, there’s only about a 20% drop from that date, the graph starts years earlier.

Dave, read the caption on the graph. It says “adjusted for inflation”. That is the key point, which is always overlooked in this debate. The data comes from the following three government sources:

TSGB0305 (ENV0105): Petrol and diesel prices and duties in April

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/761500/env0105.ods

TSGB1308: Retail prices index: transport components

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/transport-expenditure-tsgb13

Those four “raw” numbers were then indexed against the Retail Price Index:

https://www.ons.gov.uk/generator?format=xls&uri=/economy/inflationandpriceindices/timeseries/chaw/mm23

Steve: adjustments for inflation are multipliers. They can’t change proportions. Face it, the Wikigraph is a piece of faked-up propaganda.

The graph shows rates of change, not proportions.

Restore the fuel tax escalator, even if perhaps the escalator should be set at a rate which is designed not to provoke the disonaurs too much… It is so easy to implement. A lower rate of increase would give the alternatives more time to organise.